Statement at the presentation of the Deutsche Bundesbank’s 2023 Financial Stability Review

Check against delivery.

Ladies and gentlemen,

I warmly welcome you to the presentation of the Bundesbank’s Financial Stability Review this year.

In past years, we have identified vulnerabilities in the German financial system – in relation to rising credit risk and higher interest rates.

In the meantime, some aspects of these adverse scenarios have become reality.

Almost one year ago exactly, euro area inflation stood at just over 10%.[1] The Governing Council of the ECB had therefore raised key interest rates for the first time in more than a decade, to 4.5% for its main refinancing operations at last report.[2]

What impact has this sharp rise in interest rates, which barely anyone could have predicted, had in the financial system? I would like to highlight three aspects.

First, the financial system has coped with the interest rate rise well so far, but the effects have not yet fully materialised.

Second, structural change is placing demands on the financial system as well. Climate risks, geopolitical risks, demographic change and digitalisation mean that adjustments have to be made – in the real economy and in the financial system itself.

Third, this requires the financial system to be resilient enough to cope with increased risks and heightened uncertainty on its own. The good profitability situation at present offers banks the opportunity to strengthen their resilience.

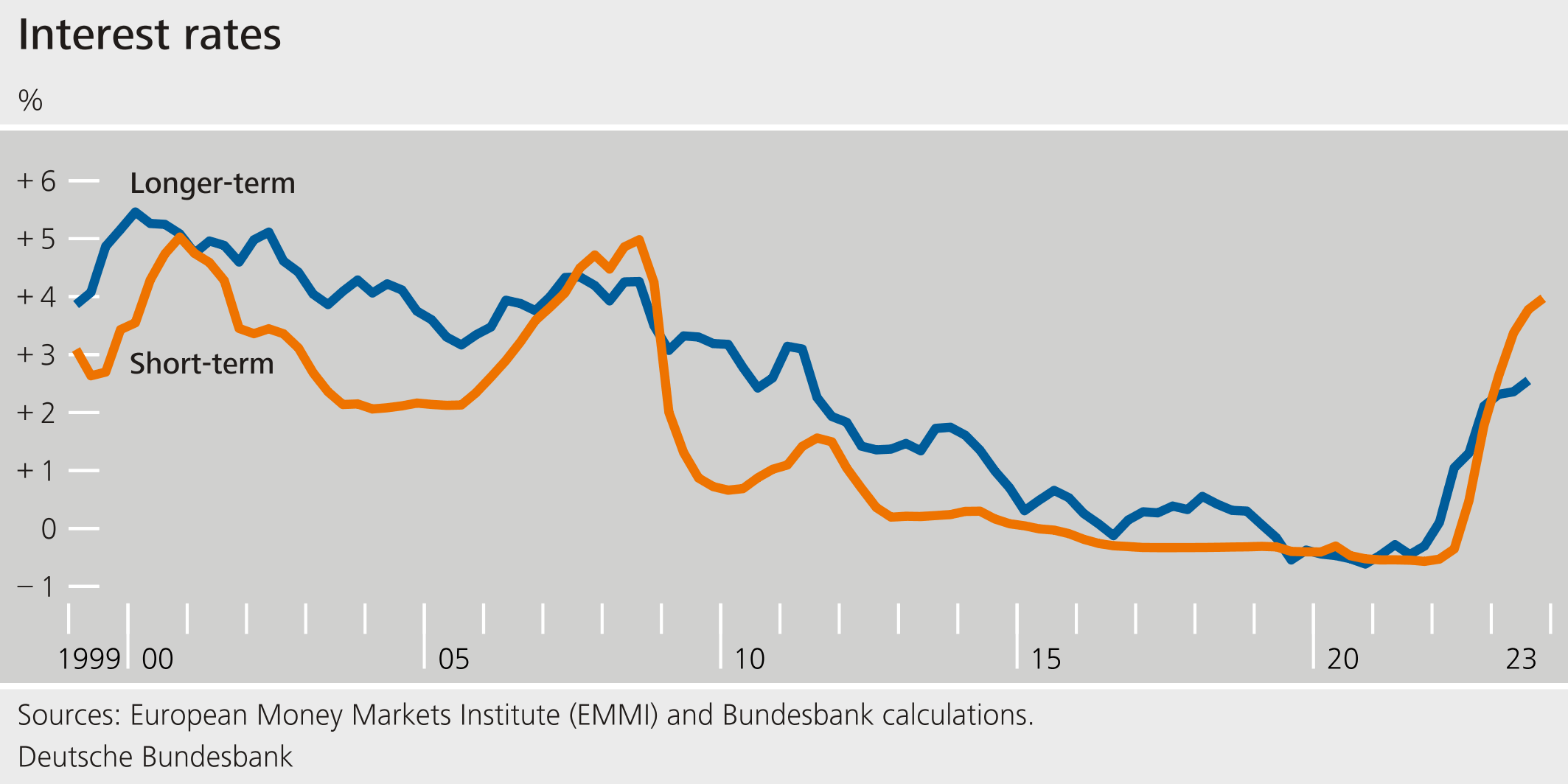

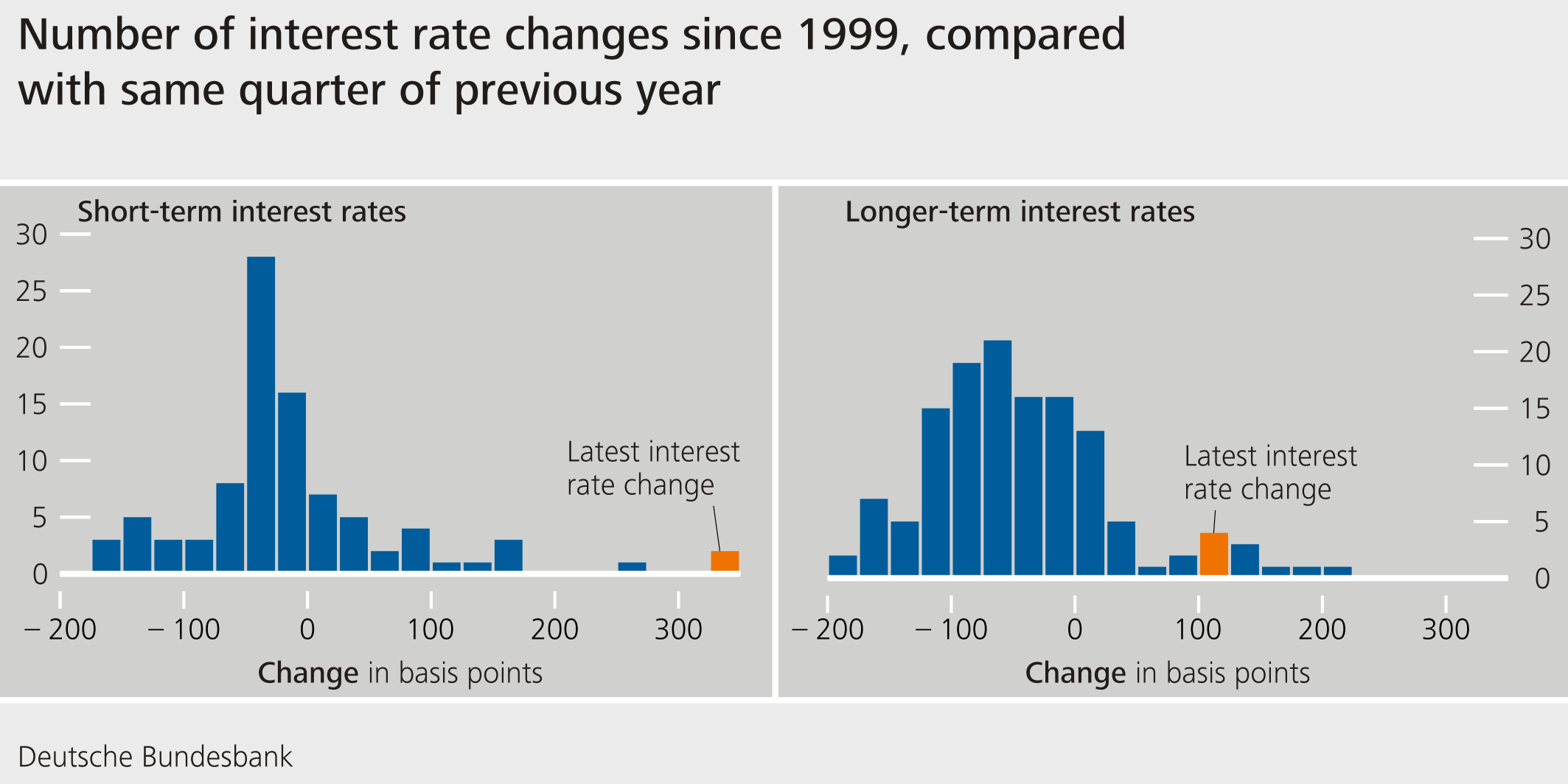

Last year, interest rates rose sharply within a very short space of time. Interest rates are currently at a level similar to that of 2005.

The interest rate rise becomes particularly apparent when looking at changes. The chart shows how often and how much interest rates have changed compared with the previous year: in most cases not changing at all, often actually falling – but an increase of more than 300 basis points in short-term interest rates, as seen recently, is virtually unprecedented over the past 25 years.

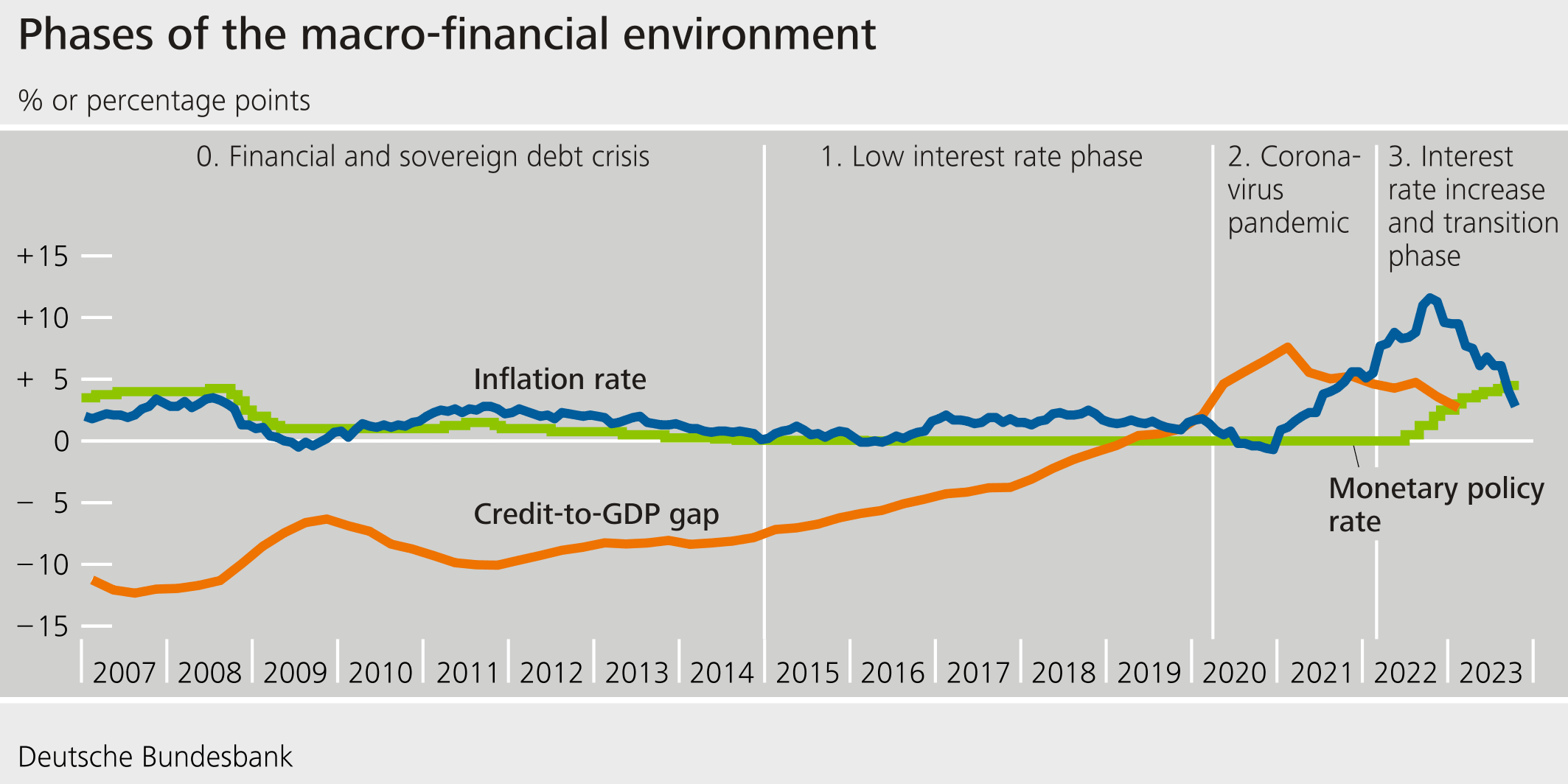

The financial system’s response to this interest rate rise is shaped by developments over recent years.

After the financial and sovereign debt crisis, interest rates were exceptionally low and economic developments stable. Insolvencies were few and there was little unemployment, credit defaults were at a historically low level. At the same time, lending was seeing dynamic growth. This made the financial system increasingly vulnerable to rising interest rates and credit defaults.

The coronavirus pandemic brought this long phase of stability to an end. Gross domestic product contracted by just under 4%. Fiscal policy, monetary policy and supervisors acted quickly, which meant that the number of insolvencies actually fell during this period. Losses for the financial system were limited. Banks did not have to use their capital buffers to absorb losses. With interest rates remaining low, lending increased.

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine marks the beginning of a third phase which we are currently in. Energy prices, inflation and thus interest rates rose significantly.[3] Economic activity is weak, especially in Germany. We expect a slight decline in GDP of 0.3% this year, while the global and euro area economy sees growth.

Growth in the German economy is slower in structural terms as well.[4]The growth rate of potential output has fallen continuously – from around 1.4% between 2000 and 2019 to less than 1% recently. The German Council of Economic Experts anticipates potential growth of no more than 0.4% for the next decade.[5]

So we are not just dealing with a spell of cyclical weakness. The economy needs to adapt to higher energy prices, geopolitical risks and demographic change. We are now setting the course for how the economy and the financial system deal with structural change. At the same time, the scope for monetary and fiscal policy has become narrower – and with it the possibilities of providing generous financial assistance during periods of stress.

1 The effects of the rise in interest rates have not yet fully materialised.

How resilient is the German financial system, then? Is it well equipped to handle structural change? We are seeing a mixed picture: the effects of the interest rate rise have not yet fully materialised.

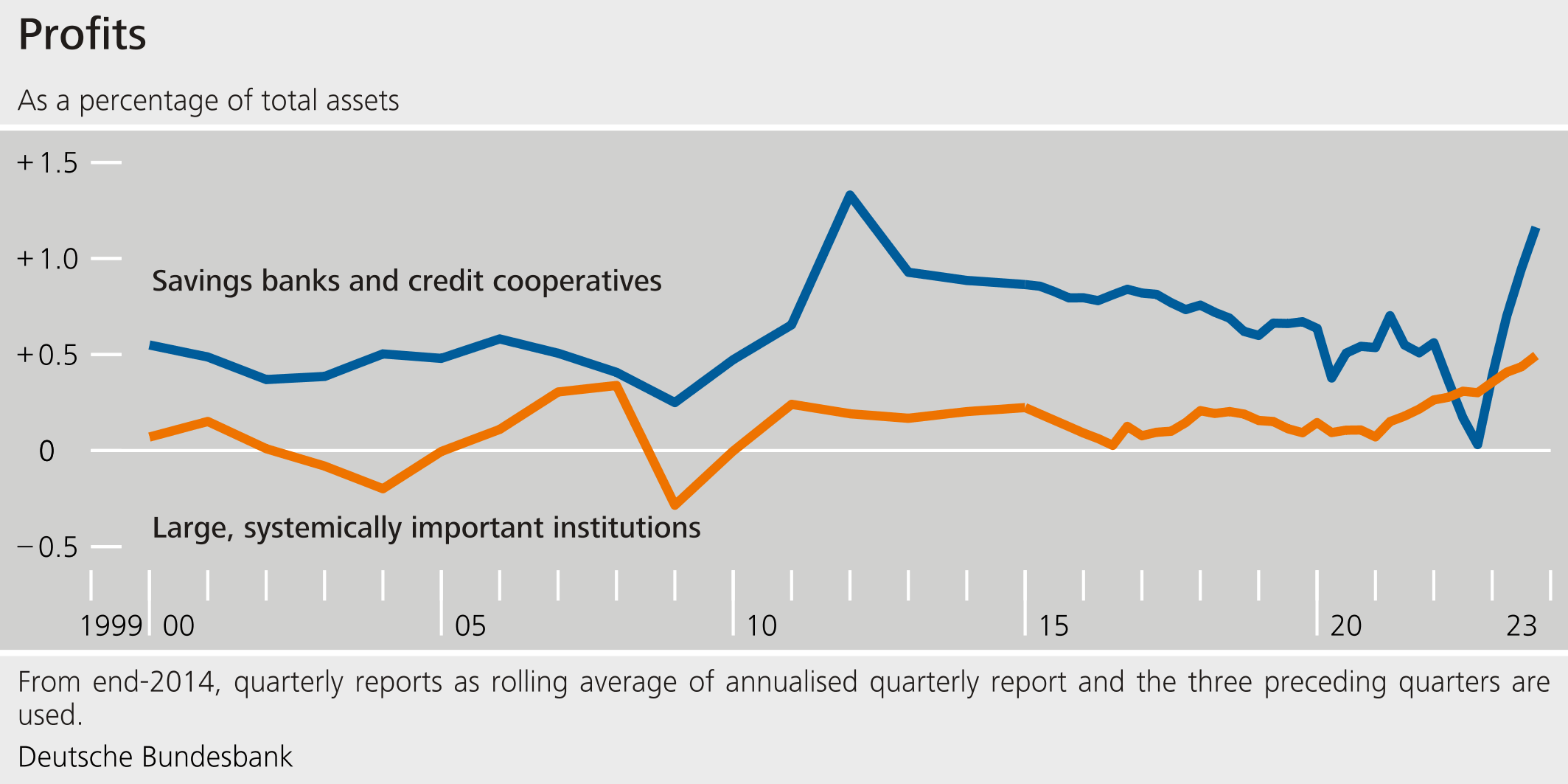

The sharp interest rate rise has already clearly left its mark, while at the same time improving the earnings situation of many financial institutions – at least in the short term.[6]

Banks’ interest margins have risen; insurers are finding it easier to generate guaranteed minimum returns.

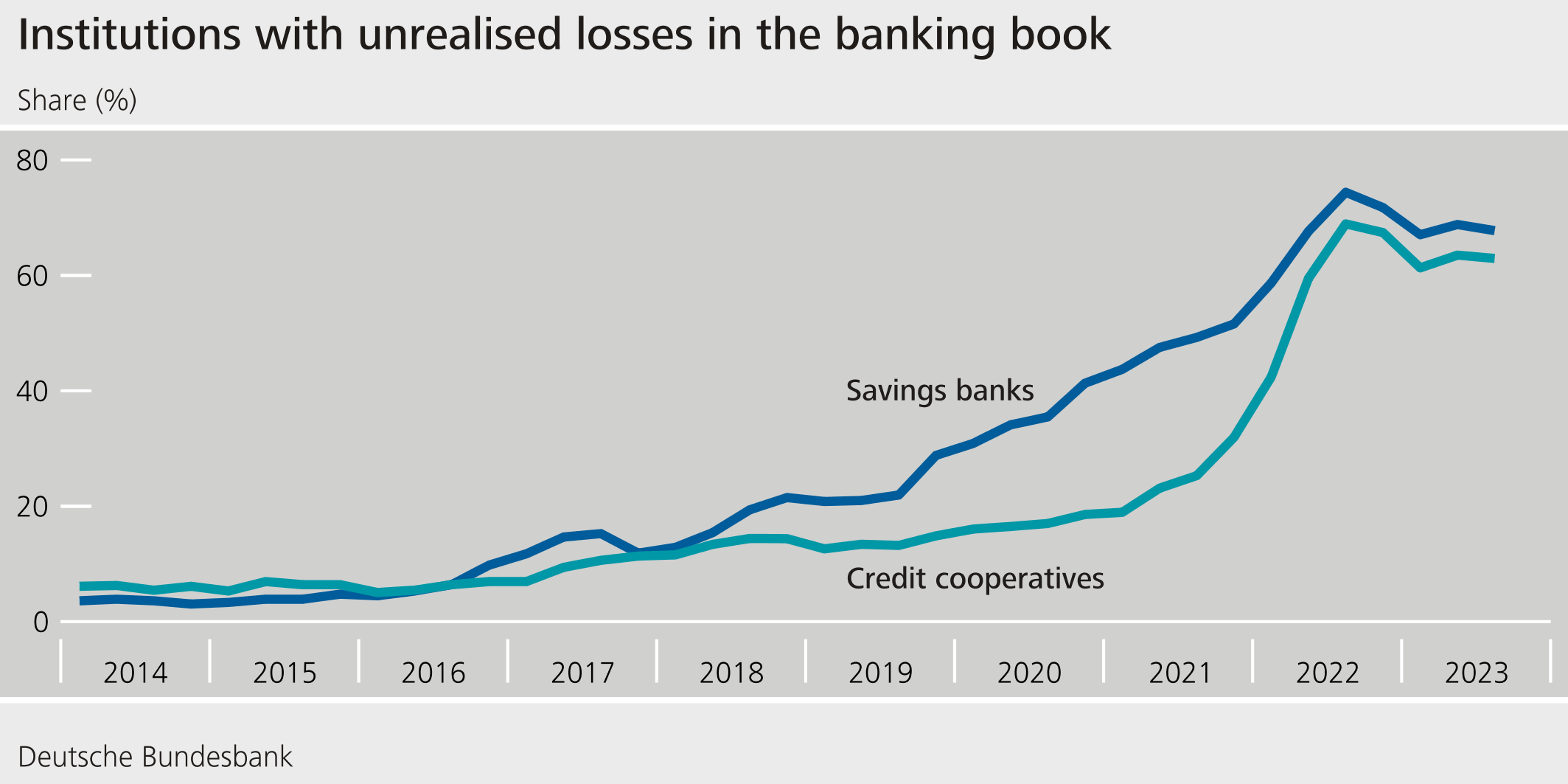

However, the revaluation of interest-bearing securities has resulted in balance sheet losses. Although hidden reserves absorbed the losses reported to date, almost two-thirds of savings banks and credit cooperatives now have unrealised losses throughout their banking book, which comprises loans as well as securities.[7]

Life insurers are in a similar situation.

In many cases, banks have been recognising securities at amortised cost.[8] However, this means that book values are often higher than current market values; selling securities would result in losses.

The resulting unrealised losses can lead to liquidity shortfalls in times of stress. Institutions may be reluctant to sell securities as a means of enhancing their liquidity and thereby realise losses. Insurers, in particular, could fail to be a stabilising factor.[9]

Overall, then, it would be premature to sound the all-clear. After all, the effects of the higher interest rates have not yet fully materialised for two reasons.

For one thing, increased cyclical risks have so far barely been priced in on financial markets. Valuations have actually increased over the course of 2023. Given the high level of macroeconomic uncertainty, there is a greater risk of market price corrections and corresponding losses.

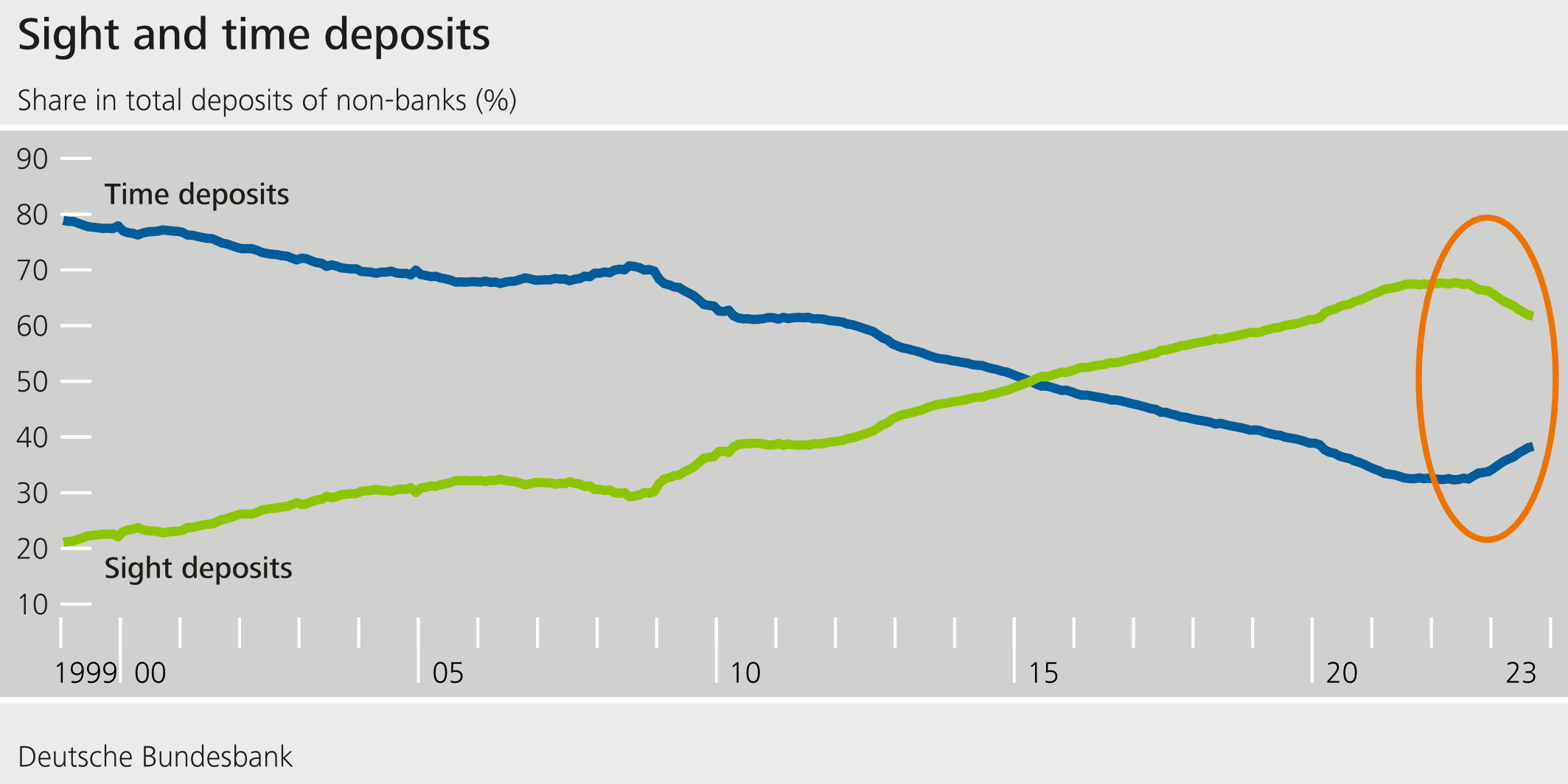

For another, banks’ interest expenditure is likely to increase. Households and firms have already shifted funds out of sight deposits and into higher-interest time deposits.

Our simulations show that if banks had passed on higher interest rates at a similar pace as they had done in the past, their net interest income this year would be €29 billion, or one-third, lower.[10]

At the same time, it is becoming more difficult to offset rising interest costs through new loans with higher rates. At present, the interest rate on the entire loan portfolio is just over 3%; the interest on new loans is around 5%.[11] In addition, weak economic activity and the high uncertainty are dampening corporate demand for loans.

We do not currently see any supply-side credit constraints. In 2023, banks’ excess capital increased year on year, with no major losses to date. Firms are increasingly reporting tighter lending conditions. However, this is primarily the banks’ response to higher credit risk and not to their own balance sheet restrictions.[12]

As in previous years, our report analyses real estate financing. In the short term, we see risks from the commercial real estate sector in particular. Risks from the financing of residential real estate are still limited, but are something that institutions and supervisors should continue to monitor closely.

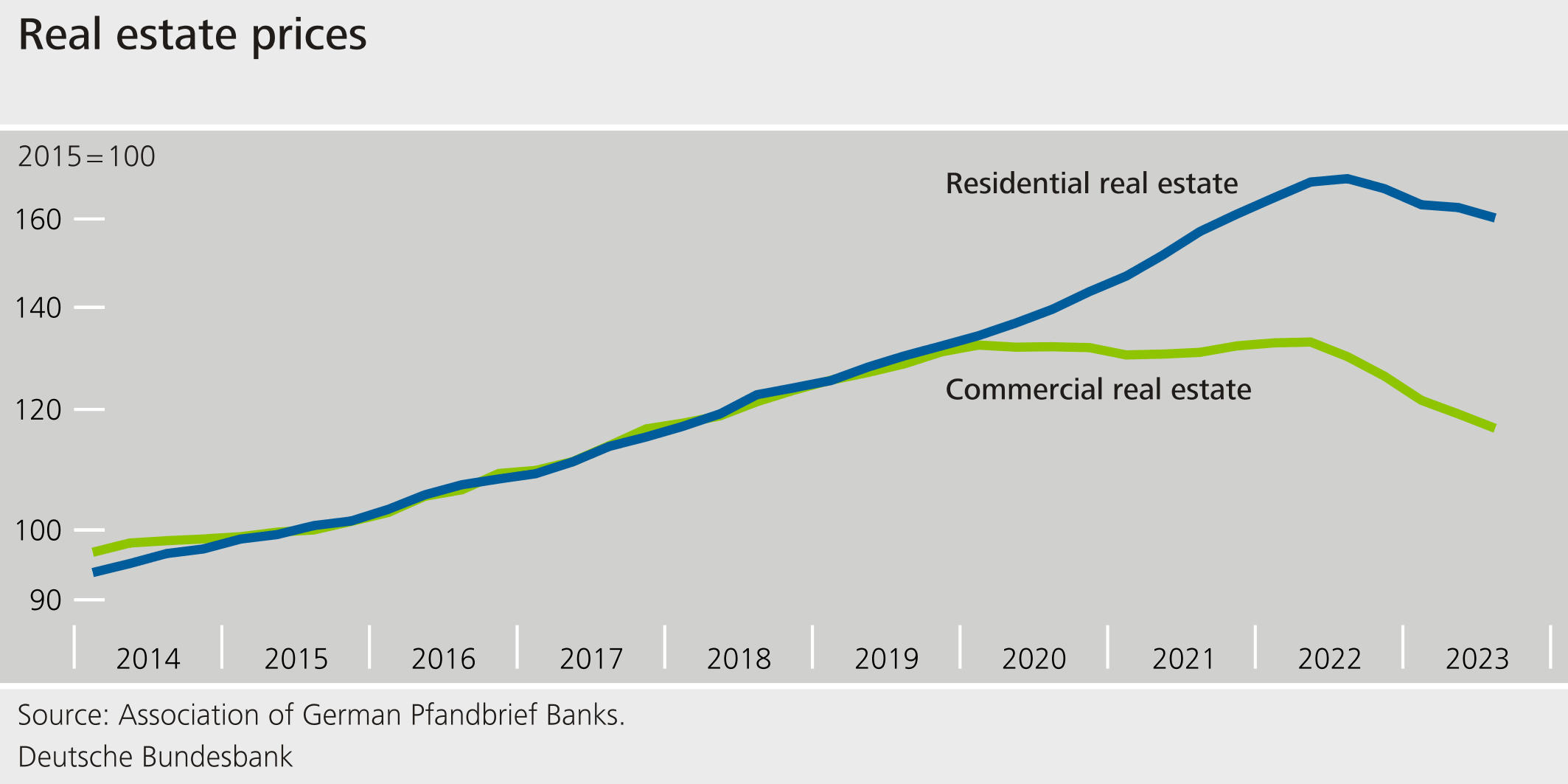

Collateral needs to be revalued throughout the real estate market, as the interest rate reversal has caused falling prices.[13]

This generally increases the risks associated with the financing of real estate.

However, risks stemming from the financing of residential real estate are limited in the short term. Demand for private real estate loans has fallen especially sharply. At the same time, however, the good labour market situation is supporting households’ debt sustainability.[14] In addition, around 40% of private real estate loans have an interest rate fixation period of at least ten years and will not need to be refinanced for roughly another five years. [15] This reduces interest rate risk for households – and shifts these risks onto banks.

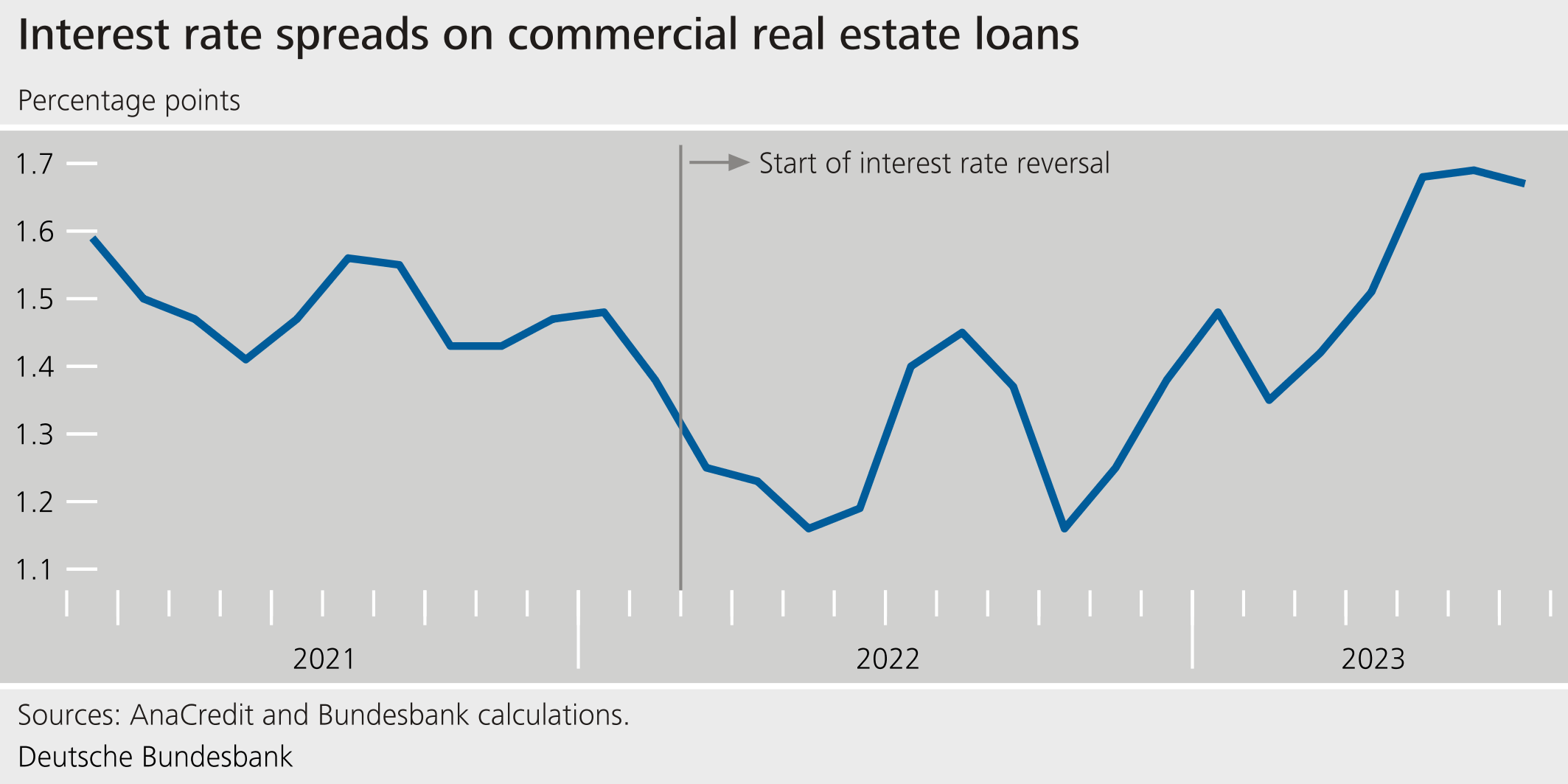

Credit risk is emanating from commercial real estate, in particular. Interest rate fixation is much shorter in this area than for residential real estate. Around one-third of loans are likely to see interest rates rise in the short term; banks are already demanding higher interest rate spreads than last year.

2 Structural change is placing demands on the financial system as well.

Overall, the financial system remains vulnerable to shocks and the challenges of structural change. Structural change means that existing patterns of investment, production and consumption are being called into question or are simply no longer profitable.[16] New business models are emerging – but we do not currently know who exactly the winners of the transformation will be. Uncertainly is high, credit, liquidity, but also cyber risks could occur simultaneously and mutually amplify each other. Financial institutions must therefore be sufficiently resilient.

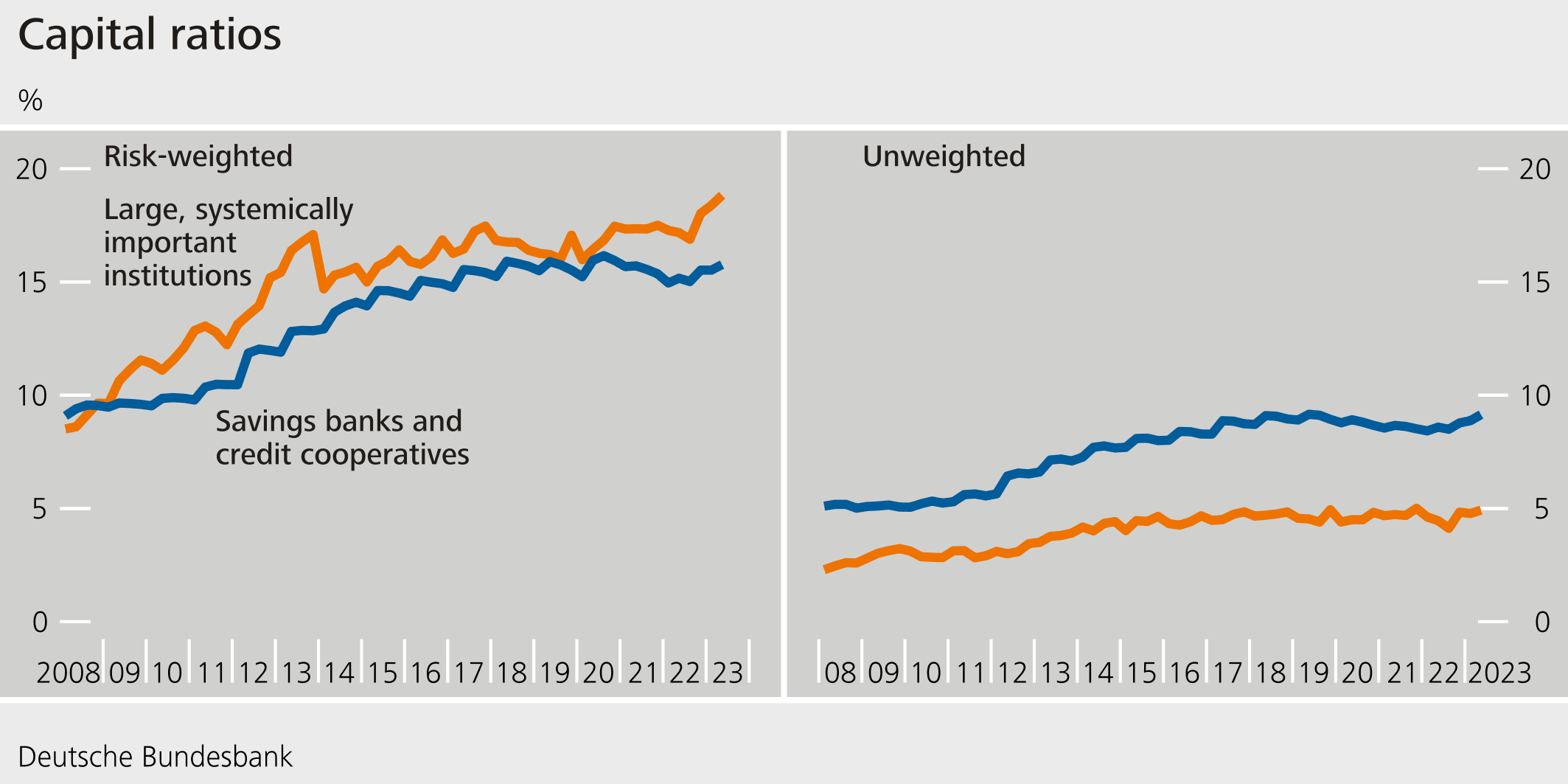

At present, German banks’ capitalisation is stable. Valuation reserves have absorbed the losses resulting from the sharp rise in interest rates. However, interest rate changes are not yet fully reflected on balance sheets – and this weighs on future profitability.

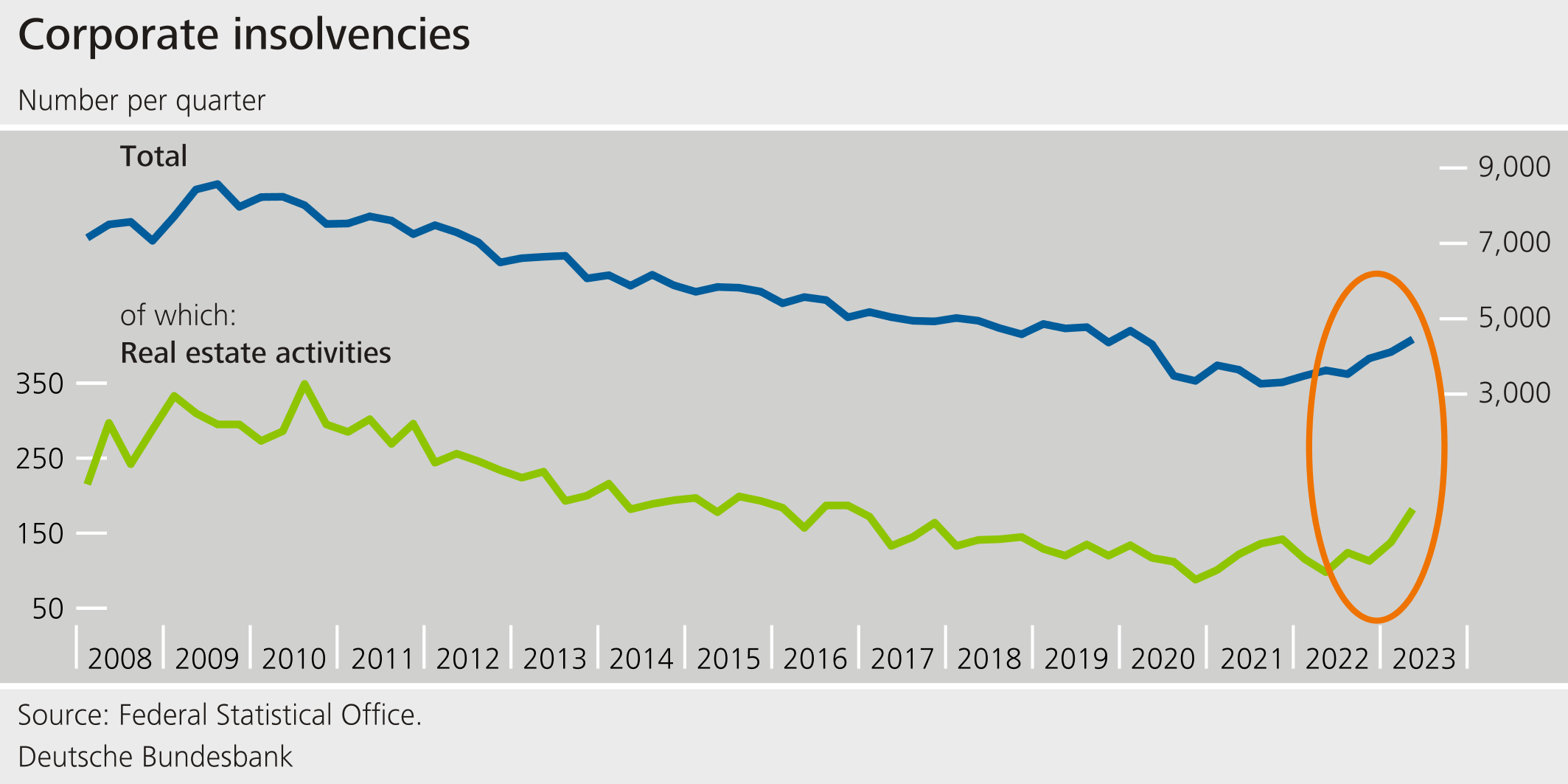

However, the structural change ahead also means more insolvencies and rising credit risks. Credit risks are likely to materialise particularly among enterprises that are highly indebted and much affected by the structural change. So far, these effects have been limited. Although corporate insolvencies rose in percentage terms, they are still well below their long-term average. Real estate activities – a key sector for banks, with a share of 30% of loans to enterprises –have been particularly hard hit by insolvencies.

Rising credit risks would drive up risk weights. This is mainly to be expected at banks that use models to determine their capital requirements. Risk-weighted capital ratios would then decline. To date, risk weights, which are used to calculate capital ratios, have hardly risen.

Savings banks and credit cooperatives have already upped their risk provisions, with specific loss allowances and non-performing loans to enterprises rising slightly for the first time in 20 years. Overall, however, loss allowances are also still at a low level from a longer-term perspective.

Two recent stress tests allow an assessment of future risks for banks.

This year’s European stress test shows that German banks would be significantly hurt by a deterioration in the economic situation. The stress test assumes a negative scenario in which economic output in Germany falls by 6.4% over a three-year period. In such a scenario, German banks’ aggregate CET 1 ratio would decline by just shy of 6 percentage points to slightly more than 10%.[17] A significant proportion of banks would fall short of supervisory capital requirements. These institutions must consequently meet higher Pillar 2 guidance in future; qualitative findings from the stress test are taken into account in the supervisory assessment.

Moreover, the stress effects do not end at the individual banks. German institutions and other European banks are interconnected. Further losses can arise via these indirect effects, meaning that the aggregate German CET 1 capital ratio could fall by another percentage point in a stress scenario.[18] Such systemic effects require macroprudential analyses and appropriate macroprudential action, like the package of measures announced last year, which included, amongst other measures, an increase in the countercyclical capital buffer.[19]

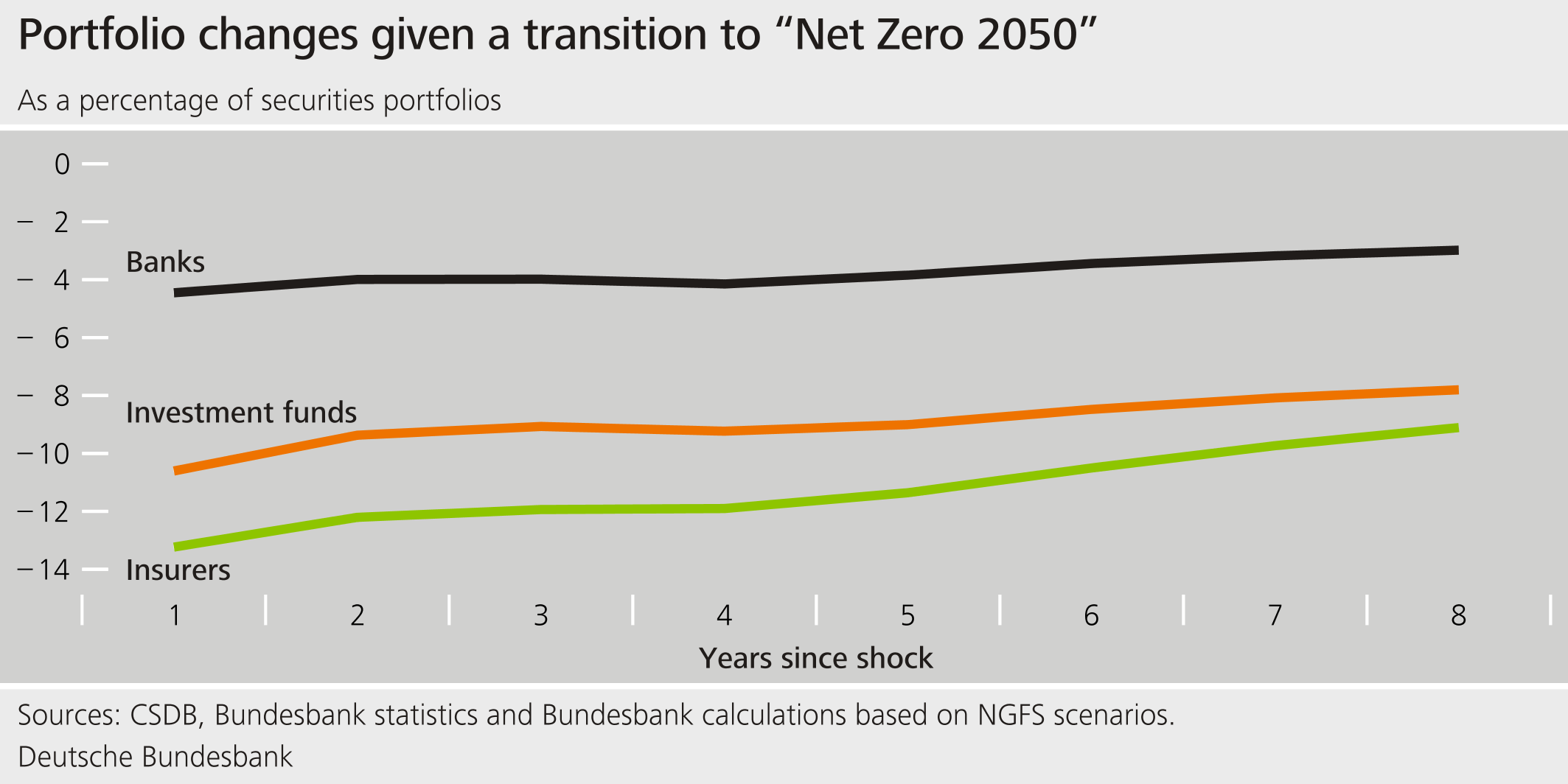

In a further stress test, we examined how climate policy transition risks could affect institutions. A global increase in the price of carbon up until 2050 that is compatible with the Paris climate targets is assumed. This would cause exposures to carbon-intensive sectors to lose value and create “stranded assets”. These risks are manageable for most financial institutions: for the banking system, losses would amount to just over 3% of CET 1 capital. Insurers and funds would record short-term market value losses, but would remain solvent.[20]

All in all, this confirms earlier Bundesbank analyses.[21]

Concerns about losses in the financial sector should therefore not stand in the way of a good climate policy. On the contrary, an orderly ecological transformation, energy transition and transparency about its consequences would spare the financial sector larger losses going forward.

Let me now turn to the third key message of our report:

3 The financial system has to be resilient enough to cope with increased risks and heightened uncertainty.

This conclusion is not new. Given the highly uncertain situation in the world, however, we need to take it particularly seriously. Just as very few observers would have predicted the extent of the interest rate reversal, so we cannot foresee today how the geopolitical situation will develop, what new enterprises and business ideas will emerge, and how and when increased credit and liquidity risks will materialise.

Dealing with this “radical uncertainty”[22] requires the cooperation of all stakeholders and preparing for negative scenarios.

The financial system should be sufficiently resilient even in periods of stress. This means that it should be adequately capitalised, liquid and protected against cyber and political risks. The higher earnings give financial institutions the opportunity to strengthen their resilience.This enables capital to be built up and investments to be made in the IT infrastructure, amongst others, not least as protection against cyber risks.

Strong, proactive supervision that reacts quickly to undesirable developments is also key. This is because crises arise – as demonstrated by the banking turmoil in March of this year – from the interplay between weak risk management on the part of institutions and macroeconomic shocks.

In terms of regulation, implementing Basel III is the priority. At the same time, we need to develop the regulatory framework in a targeted manner. Here, the focus lies on risks stemming from the growing importance of non-banks and targeted adjustments to liquidity regulation.

Over the coming years, the Bundesbank will continue to monitor risks to financial stability, identify vulnerabilities and strengthen financial institutions' resilience. The package of macroprudential measures that was announced in January 2022 is still appropriate. This package creates an additional capital buffer of just under €24 billion.[23] Almost all banks met the requirements of the package of macroprudential measures without having to create new capital. Less well capitalised banks have strengthened their capital base. We do not see any negative effects on lending or interest rates.

It would be appropriate to release the buffers only if large losses meant there was a risk of a credit crunch. In such a period of stress, banks would need their capital reserves to absorb losses. A deterioration in the economic outlook on its own is not a sufficient condition for releasing the buffers.

If all stakeholders work together successfully, the financial system can be a strong partner in managing the structural change that lies ahead. Insufficient resilience and a lack of clarity about the political and regulatory framework would exacerbate the high level of uncertainty and existing vulnerabilities.

4 List of references

Busch, Ramona and Christoph Memmel (2021), Why Are Interest Rates on Bank Deposits so Low?, Credit and Capital Markets, Vol. 54 No 4, pp. 641-668.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2023a), Monthly Report, September 2023, Frankfurt a.M.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2023b), Monthly Report, June 2023, Frankfurt a.M.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2021), Financial Stability Review, Frankfurt a.M.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2020), Financial Stability Review, Frankfurt a.M.

European Central Bank (2023), 2023 Stress Test of Euro Area Banks: Final Results, July 2023, Frankfurt a.M.

Fink, Kilian, Ulrich Krüger, Barbara Meller and Lui-Hsian Wong (2016), The Credit Quality Channel: Modeling Contagion in the Interbank Market, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 25.

Frankovic, Ivan, Hannes Wilke, Tobias Etzel, Alexander Falter, Christian Groß, Lena Strobel and Jana Ohls (2023), Climate Transition Risk Stress Test for the German Financial System, Deutsche Bundesbank Technical Paper No 04/2023, forthcoming, Frankfurt a.M.

German Council of Economic Experts (2023), Overcoming sluggish growth – Investing in the future: Annual Report 2023/24, Wiesbaden.

Hafemann, Lucas (2023), A house-prices-at-risk approach for the German residential real estate market, Deutsche Bundesbank Technical Paper No 07/2023, forthcoming, Frankfurt a.M.

International Monetary Fund (2023), Global Financial Stability Report: Safeguarding Financial Stability amid High Inflation and Geopolitical Risks, April 2023, Washington D.C.

Kay, John and Mervyn King (2020), Radical Uncertainty, Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers, W. W. Norton, New York.

Memmel, Christoph (2023), Abschätzung des Zinseinkommens der Banken in Deutschland, Deutsche Bundesbank Technical Paper No 05/2023, forthcoming, Frankfurt a.M.

Schober, Dominik, Tobias Etzel, Alexander Falter, Ivan Frankovic, Christian Gross, Anke Kablau, Pierre Lauscher, Jana Ohls, Lena Strobel and Hannes Wilke (2021), Sensitivity analysis of climate-related transition risks in the German financial sector, Deutsche Bundesbank Technical Paper No 13/2021, Frankfurt a.M.

Footnotes:

- In Germany, the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices stood at just over 11% in October 2022. See Statistics | Eurostat (europa.eu).

- This increase in the interest rate on main refinancing operations has been in force since 20 September 2023. The interest rate on the deposit facility now stands at 4% and the interest rate on the marginal lending facility at 4.75%. See ECB interest rates | Deutsche Bundesbank.

- For Germany, the Bundesbank expects inflation rates of 3.1% and 2.7% for 2024 and 2025 respectively, figures that are still above the euro area’s inflation target. See Deutsche Bundesbank (2023b).

- See Deutsche Bundesbank (2023a).

- See German Council of Economic Experts (2023).

- The significant decline in profits among savings banks and credit cooperatives in 2022 is due to losses on securities classified as current assets.

- The banking book contains all interest-bearing assets and liabilities not held in the trading book, which is to say financial instruments which are not intended to be resold short term. For the majority of the banking book, accounting rules stipulate that changes in the economic value do not have to be recognised, meaning they do not result in reported valuation losses but give rise to unrealised losses instead. These unrealised losses show that the interest on the banking book at the banks concerned is comparatively low, thus pointing to the opportunity costs of forgone investment opportunities. For savings banks and credit cooperatives, the net reduction of hidden reserves and build-up of unrealised losses represented 14.2% of common equity tier 1 (CET 1) capital at the end of 2022. Other systemically important institutions reported unrealised losses totalling 5.8% of their CET 1 capital. Sources: harmonised financial reporting requirements (FINREP), Common Reporting Framework (COREP), GVKI (financial information pursuant to Section 25(1) sentence 1 of the German Banking Act – profit and loss account).

- Savings banks and credit cooperatives reclassified securities from current to long-term assets. The share of securities classified as long-term assets increased from 14% at the end of 2021 to 44% at the end of 2022. Other systemically important institutions, which report in accordance with IFRSs, reclassified securities into the amortised cost measurement category. Over the course of 2022, this category’s share grew from around 32% to roughly 41%. Source: harmonised financial reporting requirements (FINREP).

- During the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, while banks and investment funds sold low-rated securities whose prices had fallen sharply, life insurers countercyclically increased their holdings of these securities. At the same time, they reduced their holdings of lower-risk securities whose prices had fallen. See Deutsche Bundesbank (2020, 2021).

- See Memmel (2023) and Busch and Memmel (2021).

- As at September 2023. Source: analytical credit datasets (AnaCredit).

- The German banks surveyed in the Bank Lending Survey (BLS) report that their more restrictive credit standards were motivated by the higher general level of interest rates and higher credit risk perceptions; see the October results of the Bank Lending Survey for Germany | Deutsche Bundesbank.

- According to estimates, around the time of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, prices for residential real estate in urban areas remained between 15% and 30% above the level suggested by the demographic and economic fundamentals; see Deutsche Bundesbank (2021). In 2022, this figure was between 20% and 30%; see Deutsche Bundesbank (2023b). A house-price-at-risk model for Germany shows that there could still be a certain degree of downside potential for nominal house prices in the short term; see Hafemann (2023).

- Household debt declined slightly to 95% of disposable income this year – mainly owing to weaker lending; see System of indicators for the German residential property market | Deutsche Bundesbank.

- This figure refers to March 2023. In 2019, the corresponding share was still more than 50%. This is calculated as domestic banks’ volume of new lending business with the respective rate fixation period as a share of new business.

- See Deutsche Bundesbank (2023a) and International Monetary Fund (2023).

- See European Central Bank (2023) and EU-wide stress testing | European Banking Authority (europa.eu).

- The banking system loss model is used to quantify such contagion effects; see Fink et al. (2016). Banks’ adjustment responses, such as balance sheet reductions, and stabilising measures are disregarded.

- See Federal Financial Supervisory Authority – Countercyclical capital buffer.

- See Frankovic et al. (2023).

- See Schober et al. (2021).

- Kay and King (2020).

- As at the end of June 2023. Source: Common Reporting Framework (COREP).