How the design of own funds requirements can influence banks’ behaviour Research Brief | 69th edition – September 2024

Global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) have to comply with additional buffer requirements owing to their size and interconnectedness within the banking sector. The buffer level banks are expected to meet depends on their exposures at a certain point in time. A new study shows that G-SIBs reduce their exposures more strongly – twice as strongly, in fact – than other banks at period-end reporting dates. As a result, the buffer level may be too low to cover the additional risk associated with G-SIBs.

The global financial crisis of 2007‑09 saw a number of large, internationally active and highly interconnected banks run into difficulties. The resulting spillover effects produced additional turmoil in the global financial system and ultimately in the real economy as well. Some of these large banks received financial support from governments concerned about the fallout that might ensue if these institutions, which were considered particularly important to the stability of the global financial system as a whole, became insolvent.

Stability of large and interconnected banks particularly important to financial system

To ensure that G-SIBs will ideally no longer need government support going forward and to increase their resilience to stress situations, these institutions are required to meet an additional capital requirement, known as the G-SIB buffer. The idea behind this instrument is to cover the additional risk associated with G-SIBs and create an incentive for G-SIBs to reduce their systemic importance in the future. G-SIBs are categorised into buckets that are subject to G-SIB buffer surcharges of between 1.0% and 3.5%. Which G-SIB buffer surcharge is applied depends on multiple indicators, such as the notional amount of derivatives, at a specific point in time. However, assessing mostly stock variables at a given point in time (usually year-end) in isolation can give banks an incentive to engage in window dressing – that is, to deliberately reduce their exposures at that point in time and thus lower their additional loss absorbency requirement.

Window dressing can contribute to banks’ lack of own funds

While the purpose of the additional own funds requirement for G-SIBs has generally been welcomed, there is also criticism directed at the focus on a certain point in time and the incentives this generates to engage in window dressing behaviour. This, the critics say, could mean that banks’ own funds ratios are too low, leaving them more vulnerable to crises. The debate surrounding the design of the additional loss absorbency requirement for G-SIBs flared up particularly in the wake of UBS’s acquisition of Credit Suisse in 2023. This acquisition came after Credit Suisse ran into difficulties and saw the Swiss National Bank provide liquidity assistance. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is also talking about adjusting the methodology used for determining the additional loss absorbency requirement such that an average of intra-year values would be used, rather than a single point-in-time value (see Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2024).

G-SIBs do more window dressing than other banks

Our study explores whether G-SIBs do more window dressing than other banks when the G-SIB buffer requirement is determined mostly based on point-in-time assessments. We examine large, internationally active banks from different jurisdictions over an eight-year period. The exposures covered by our analysis, which are used to determine the additional loss absorbency requirement, comprise bank size as measured by total assets, debt securities outstanding, derivatives, Level 3 assets, and trading and available-for-sale securities. We find that G-SIBs reduce their exposures more strongly – twice as strongly, in fact – than other banks at year-end. In addition, we observe that G-SIBs increase these exposures again more strongly than other banks at the beginning of the year.

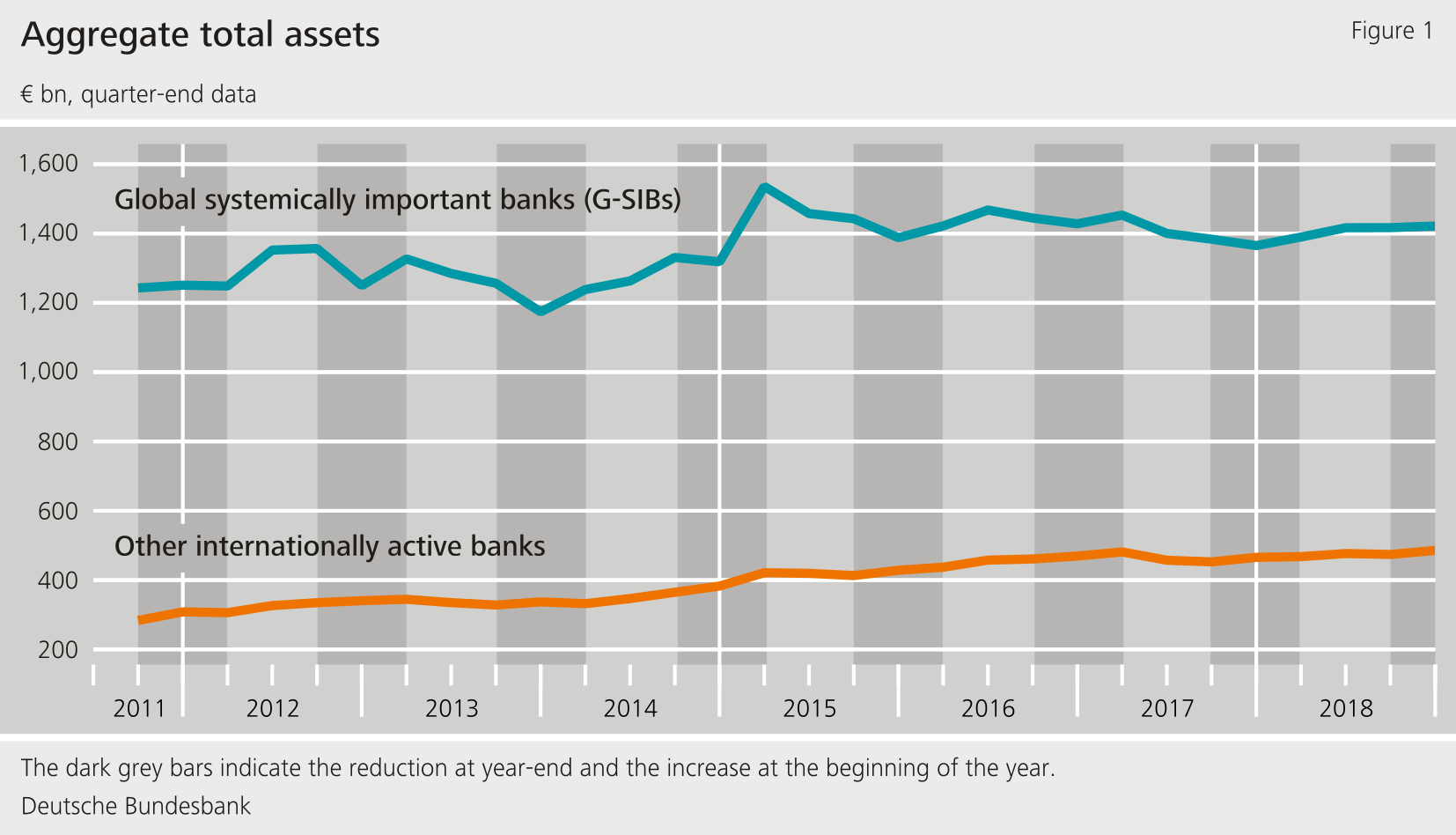

Our key finding is illustrated in Figure 1. Using movements in aggregate total assets for illustrative purposes, this figure shows that G-SIBs reduce their total assets more strongly at year-end and increase them again more strongly at the beginning of the year than other banks. This behaviour shows that G-SIBs engage in more window dressing than other banks. Our research finds that this is particularly the case for G-SIBs that are in close proximity to a higher or lower additional loss absorbency requirement or were already required to meet a high buffer requirement beforehand. Other studies arrive at similar findings (see Behn, Mangiante, Parisi and Wedow, 2022; Garcia, Lewrick and Sečnik, 2023; and Naylor, Corrias and Welz, 2024).

Conclusion

Our analysis explores, based on the G-SIB framework, whether the design of additional loss absorbency requirements might influence banks’ behaviour. Our results confirm that it does. We find that G-SIBs reduce certain exposures more strongly at year-end than other banks and increase them again more strongly at the beginning of the year – roughly twice as strongly in each case. This is indicative of window dressing behaviour. It is welcome news, then, that the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is thinking about determining the additional loss absorbency requirement for G-SIBs based on an intra-year average value rather than the current point-in-time value as part of the revision of the methodology.

| Disclaimer |

| The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem. |

References

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2024). Consultative Document: Global systemically important banks – revised assessment framework, Bank for International Settlements, March 2024.

- Behn, M., G. Mangiante, L. Parisi and M. Wedow (2022). Behind the scenes of the beauty contest – window dressing and the G-SIB framework. International Journal of Central Banking, 18, 301‑342.

- Garcia, L., U. Lewrick and T. Sečnik (2023). Window Dressing and the Designation of Global Systemically Important Banks, Journal of Financial Services Research, 64, 231‑264, September.

- Naylor, M., R. Corrias and P. Welz (2024). Banks’ window-dressing of the G-SIB framework: Causal evidence from a quantitative impact study, BCBS Working Paper 42.

News from the Research Centre

Publications

- “Time-varying return correlation, news shocks, and business cycles“ by Norbert Metiu (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Esteban Prieto Fernandez (Deutsche Bundesbank) will be published in the European Economic Review.

- “The Hockey Stick Phillips Curve and the Effective Lower Bound” by Philipp Lieberknecht (Deutsche Bundesbank) and Gregor Boehl (Universität Bonn) will be published in the Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control.

Events

- Spring Conference on Expectations of Households and Firms

24. – 25.04.2025 | Eltville am Rhein

492 KB, PDF