Tackling too-big-to-fail banks: Have the reforms been effective? Remarks by Claudia M. Buch, Vice-President, Deutsche Bundesbank at a Bruegel online discussion

Check against delivery.

Motivation

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, the G20 endorsed a number of reforms intended to make the financial system safer. The Financial Stability Board is evaluating the “too-big-to-fail” (TBTF) reforms for systemically important banks (SIBs). The working group that is carrying out the evaluation has published a report for consultation on 28 June. The public consultation of the evaluation closes on 30 September and we would encourage responses from a wide range of stakeholders from the private sector, academia, and civil society.

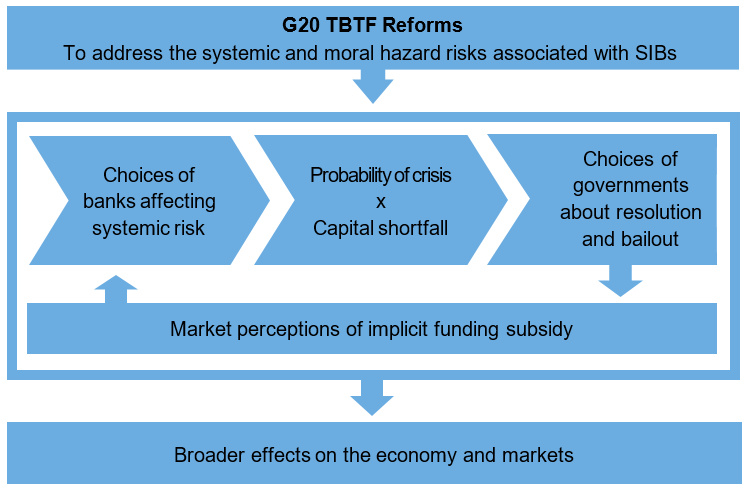

Let’s first recall the situation at the time of the 2008 financial crisis. Banks were weakly capitalised, resolution regimes for banks were missing, and taxpayers’ money was often used to bail out banks. The expectation of government support acts as an implicit subsidy: it lowers the financing costs of systemically important banks and weakens market discipline because risks are not adequately priced. It creates incentives for these banks to take too much risk – we call this moral hazard.

The TBTF reforms are intended to reduce this moral hazard and systemic risk through:

- Standards for additional loss absorbency through capital surcharges and total loss-absorbing capacity requirements;

- Recommendations for enhanced supervision and heightened supervisory expectations; and

- Policies to put in place effective resolution regimes and resolution planning to improve the resolvability of banks.

Because systemic risk and moral hazard are not directly observable, the evaluation focuses on the mechanisms through which the reforms are expected to operate. The systemic importance of banks depends, for example, on their choices over size, assets, structure, funding, and risk. Higher capital requirements and more intensive supervision can encourage banks to internalise their externalities and change behaviour. Bank behaviour, in turn, determines the system-wide probability of a crisis, the capital shortfall and the amount of recapitalisation needed, and the expected loss to the economy. In the absence of effective frameworks for resolution, public authorities are not able to credibly commit to allowing SIBs to fail. SIBs may thus enjoy funding cost advantages over other banks, market discipline may fail to constrain SIBs’ risk-taking, and market structures and competition may be distorted. These feedback mechanisms affect aggregate outcomes such as the overall resilience of the financial system and the provision of finance.

There are two types of systemically important bank: global systemically important banks or G-SIBs, and domestic systemically important banks or D-SIBs. There are about 30 G-SIBs – the FSB publishes a list of them every year. D-SIBs are designated by their home authorities and their number stood at 132 at the last count (2018), 40 of them being headquartered in the EU, the UK, and Switzerland, and 25 in the EU alone.

The central questions of the evaluation are whether the reforms have achieved their objectives, and whether there were any unintended side-effects. Let me also clarify what is not included. First, the evaluation focuses on the too big to fail reforms that I just mentioned. They were plenty of other post-crisis reforms, such as the Basel III standards, or the clearing obligation for standardised over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, but we have not evaluated them. Second, the evaluation was completed before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The overall findings of the evaluation can be summarised under three headlines:

- Indicators of systemic risk and moral hazard have fallen;

- Effective TBTF reforms bring net benefits to society; and

- There are still gaps that need to be addressed.

What does the report say about how resilient banks are?

TBTF reforms have made banks more resilient and resolvable. Systemically important banks are better capitalised and can absorb more losses:

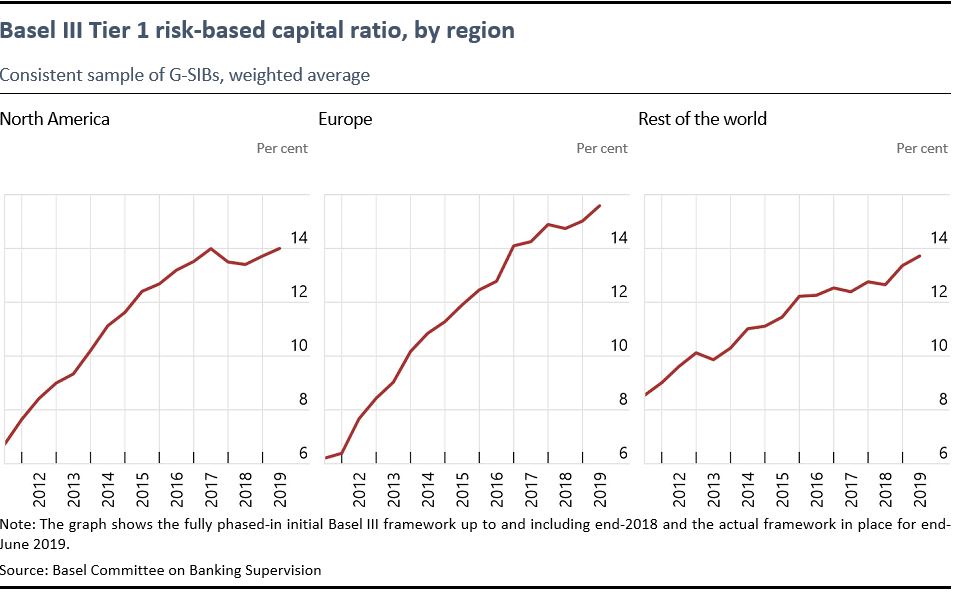

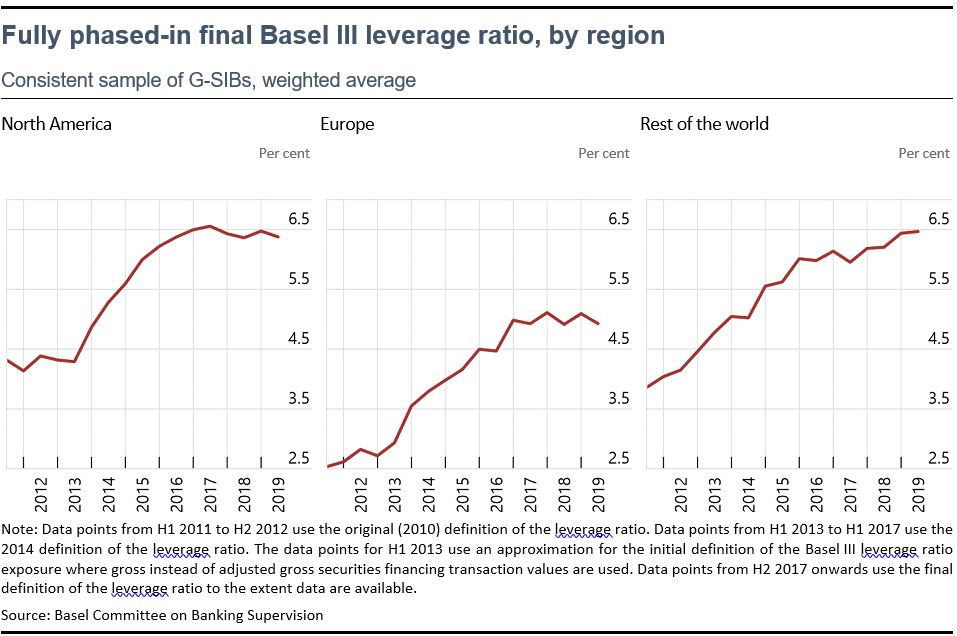

- The capital ratios of G-SIBs relative to banks’ risk-weighted assets have doubled since 2011; in Europe the improvement is larger than elsewhere.

- The picture is a little different if we look at the leverage ratio. Leverage ratios have also risen markedly everywhere, but they have always been, and continue to be, lower in Europe: ratios are 5% here, against an average of 6.5% elsewhere.

- G-SIBs have also issued large quantities of debt that is capable of absorbing losses in resolution and are meeting their minimum requirements for such loss-absorbing capacity.

Changes in bank profitability are in line with expectations. Higher equity capital, lower risk, and higher funding costs for systemically important banks would be expected to lower banks’ return on equity. In this sense, lower bank profitability can be in line with a more robust banking system and with lower costs for the taxpayer. Before the 2008 financial crisis, banks that were considered to be too-big-to-fail in effect enjoyed an implicit subsidy from the state. This is a costly economic distortion, and the reforms aim to reduce this subsidy. If the reforms are having an impact, we would expect to see the profitability of G-SIBs fall relative to other banks, all other things equal. At the same time, low profitability of banks can also be an indicator of excess capacity in the banking sector and lack of exit – an issue that resolution reforms may help to address.

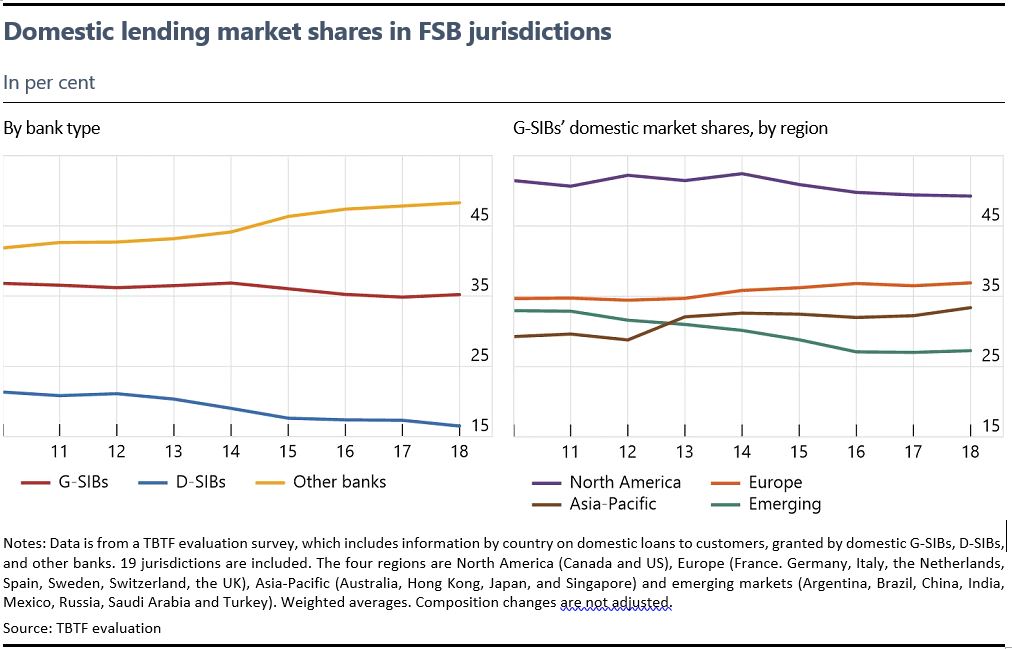

Domestic market shares of systemically important banks have fallen globally. This is, again, largely an expected outcome of the reforms as systemically important banks can be expected to reduce the volume of activities as subsidies are withdrawn. In Europe, market shares of systemically important banks have not moved much.

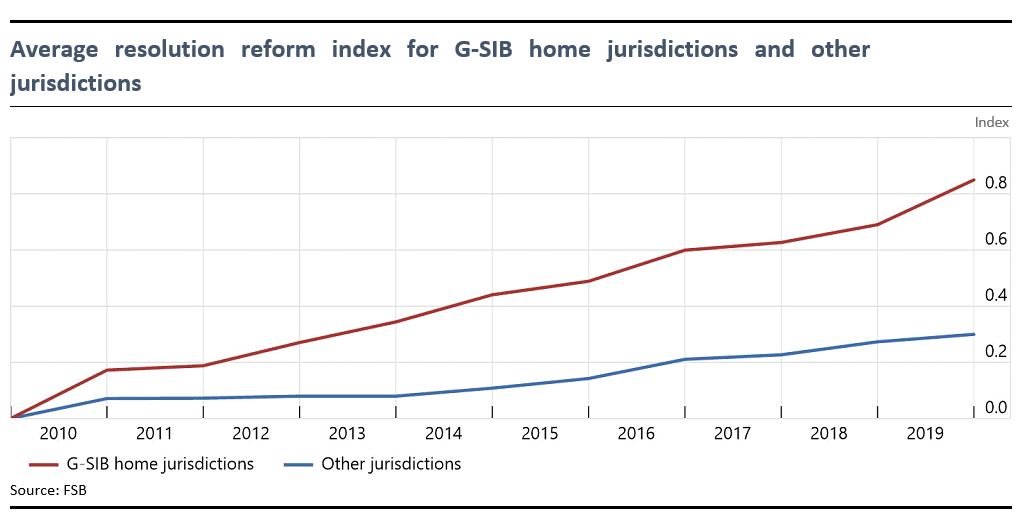

Another central plank of the reforms has been the establishment of resolution frameworks. Resolution is a way for authorities to deal with a failing bank without bailing it out and without disrupting its critical economic functions – typically by imposing losses on shareholders and creditors. Jurisdictions that are home to G-SIBs have made good progress in implementing resolution reforms. They have almost all introduced comprehensive bank resolution regimes and are now carrying out detailed resolution planning. This gives authorities a range of options for dealing with banks in stress. The EU scores highly too. The EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) in effect implemented the relevant global standard in 2014. Some EU jurisdictions had implemented their own frameworks even before BRRD came into effect.

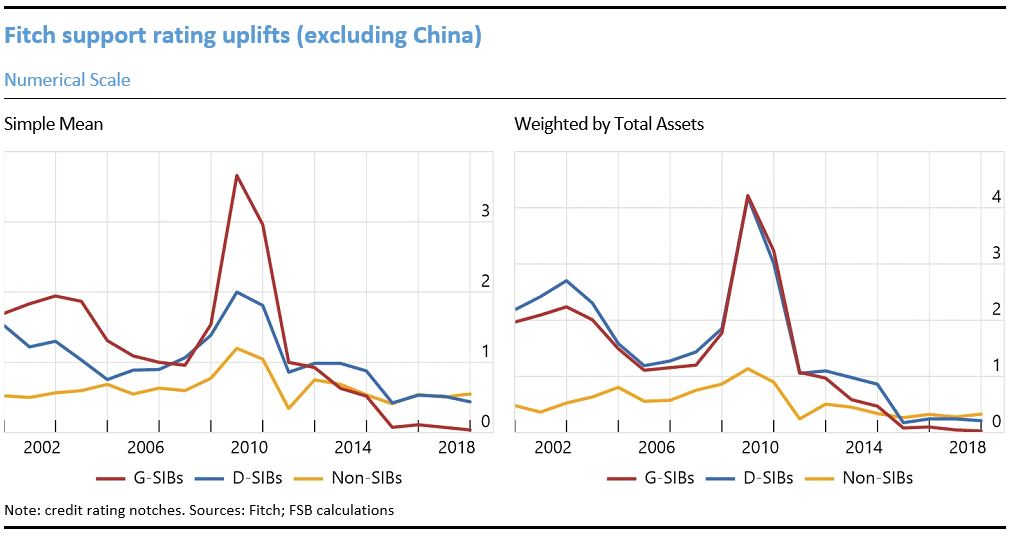

Evidence from market prices and credit ratings suggest that resolution reforms are seen as credible by market participants. By this I mean that market participants think that there is some probability that, in the event of a bank failure, losses would be imposed on shareholders and creditors rather than on taxpayers.

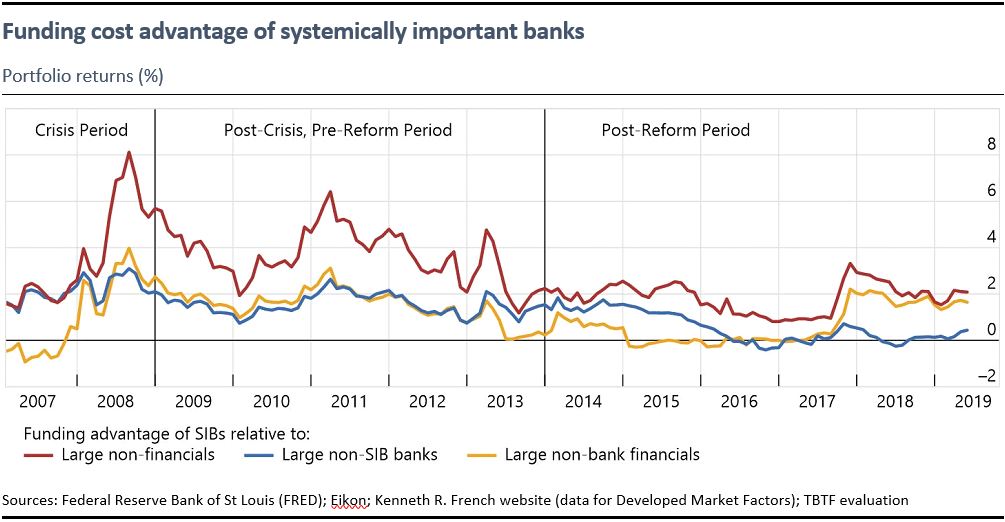

Changes in perceptions of the credibility of resolution are hard to measure, and the evaluation has used different proxies. Our first analysis is funding cost advantages. We have estimated G-SIBs’ funding cost advantages by looking at prices of bonds, credit default swaps and equities. Inevitably, the results are not identical, but in the main they show that funding cost advantages peaked during the global financial crisis and have since fallen, although not below levels seen before the crisis. Lower funding cost advantages indirectly suggest that the holders of these instruments are not betting on a government bail out in the event of a bank failure.

Estimated funding cost advantages are also lower, on average, in jurisdictions that have implemented resolution reforms more fully, perhaps because investors assume they are at greater risk of experiencing losses in the event of bank failure. This suggests that more comprehensive implementation of resolution reforms is associated with a reduced funding advantage for SIBs, and hence with less economic distortion.

Most of our results are based on samples that extend beyond Europe. We did carry out a study of pricing of bond market issuance in Europe. Interestingly, this study finds no evidence of a funding cost advantage for systemically important banks. It would be useful for future work to look more into potential reasons for this finding, such as structural differences between primary and secondary markets, institutional investors’ risk appetite as well as differences between systemically important banks.

Our second analysis uses bank credit ratings. These comprise two elements: a bank’s stand-alone strength, and its likelihood of receiving external support in the event of failure. The possibility of support means that the overall rating is typically higher than on a stand-alone basis, which lowers the cost of funding for banks that are expected to receive state support. The gap between these two ratings has fallen in aggregate. But it varies across jurisdictions and is lower in jurisdictions that have implemented resolution reforms more fully.

Our third analysis looks at bank debt that is subordinated – that is, further back in the queue for repayment in the event of an insolvency, and thus more likely to bear losses in the event of failure. G-SIBs now have to comply with minimum requirements for resources that can bear losses and recapitalise the bank in the event of its failure. This is known as total loss-absorbing capacity, or TLAC. One study[1] compares the prices of bail-inable bonds that count as TLAC with senior unsecured bonds that do not count as TLAC and are less likely to be bailed in when a bank fails. It found that investors are demanding a risk premium on the TLAC-eligible debt of G‑SIBs. This suggests that investors are at least partially pricing in the risk of G-SIB failure and a potential bail-in.

This difference in the costs of the two types of debt is larger for banks that have taken on more risk, as we would expect. We find a similar result when we look at the price of credit default swaps - which offer insurance against the failure of a bank with swap spreads larger for riskier banks. Both of these results suggest that market discipline is operating.

What does the evaluation find about costs and benefits?

The evaluation finds that the benefits of the reforms significantly outweigh the costs. The evaluation looked at broader effects of reforms on the financial system and on the real economy. It also examined costs and benefits from the social perspective, which is not the same as the perspective of the private sector. For example, if we successfully lower implicit subsidies, that means higher funding costs for banks - but at the same time lower costs for taxpayers.

Estimates of the macroeconomic costs and benefits of the too-big-to-fail reforms suggest that the reforms have produced net benefits to society. This is because they reduce the probability and costs of financial crisis, the economic and social impacts of which are persistent and very large.

We do not observe material side-effects on aggregate lending. Some respondent to our call for public feedback in 2019 argued that too-big-to-fail reforms have depressed lending.[2] We tested this hypothesis, and the evidence does not support it. SIBs have lost domestic market share, but they have not reduced their lending. In advanced economies, their lending has moved in step with economic output and in emerging markets it has increased faster than economic output. Other market participants – both banks and non-banks – have increased lending relative to economic output. The evaluation shows that aggregate credit has therefore risen as a proportion of economic output. Previous evaluations by the FSB, such as the one on the effects of reforms on SME financing, have reached similar conclusions.[3]

Market fragmentation has not increased. The 2007-08 financial crisis slowed down, but did not reverse, the long-term trend towards global financial integration. We do not see falls in cross-border bank activity other than in Europe. It seems likely that other factors drove retrenchment in Europe, notably the sovereign debt crisis. Lending by international banks has shifted to more stable locally-funded sources in local currencies. Measures of cross-border connections between banks have returned to or surpassed their pre-crisis levels. Cross-border lending by advanced economy banks to borrowers in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) has grown since the crisis, and intraregional lending has also increased within EMDEs, in particular in Asia and Latin America. The evaluation also did not find evidence to support the hypothesis that internal TLAC has fragmentary effects, though the benefits in terms of supporting orderly resolution and incentivising coordination between home and host authorities are clear.

What remains to be done?

A great deal of progress has indeed been made: resolution regimes for banks did not exist prior to the global financial crisis, we now have internationally agreed resolution standards and cross-border cooperation agreements, while the funding structure of large banks has changed. We are still learning how the new system for the regulation of systemically important banks is working in practice, and where it can be improved.

The FSB has developed the policy elements of addressing the TBTF problem. But the focus must now be on effective implementation. The evaluation helps to identify further areas for work. There are still gaps that need to be addressed.

First, resolution of systemically important banks is a complex process, and some obstacles to resolvability remain. These involve internal TLAC implementation; resolution funding mechanisms; the valuation of bank assets in resolution; operational continuity and continuity of access to financial market infrastructure; and cross-border coordination. The FSB continues to work on these.

Second, gaps in our knowledge need to be closed. Not least as a result of recovery and resolution planning, supervisors and firms have much better information than they did before the implementation of the reforms. However, market participants consider disclosure of matters relating to resolution, including resolution strategies, who bears losses in resolution, resolution funding arrangements, or authorities’ resolvability assessments as being insufficient. For example, we did not find good information on who owns TLAC issued by G‑SIBs, which is needed if we are to assess the potential impact of a bail-in on the financial system and the economy.

Third, the application of the reforms to domestic systemically important banks warrants further monitoring. Many D-SIBs operate across borders and threats to their resilience may therefore affect financial stability in more than one jurisdiction. Yet, compared to G-SIBs, relatively little is published by national authorities and at the international level about D-SIBs’ characteristics or the regulations to which they are subject. Information on D-SIBs and on prudential measures applied to them would be useful.

Fourth, risks arising from the shift of credit intermediation to non-bank financial intermediaries should continue to be closely monitored. As these institutions have picked up market share, some risks have moved outside the banking system. This shift may enhance the stability of the financial system, partly because it may lead to a diversification of funding sources. However, it could also be a source of financial instability. The shift to non-bank financial intermediation reinforces the importance of continuing to assess vulnerabilities and developing policies to address financial stability risks.

Further reading

FSB TBTF consultation report:

https://www.fsb.org/2020/06/evaluation-of-the-effects-of-too-big-to-fail-reforms-consultation-report/

FSB evaluation framework:

https://www.fsb.org/2017/07/framework-for-post-implementation-evaluation-of-the-effects-of-the-g20-financial-regulatory-reforms/

Findings of earlier evaluations:

https://www.fsb.org/2019/11/evaluation-of-the-effects-of-financial-regulatory-reforms-on-small-and-medium-sized-enterprise-sme-financing-final-report/

https://www.fsb.org/2018/11/incentives-to-centrally-clear-over-the-counter-otc-derivatives-2/

Fußnoten:

- Lewrick, U, J Serena and G Turner (2019): “Believing in bail-in? Market discipline and the pricing of bail-in bonds”, BIS Working Papers, no. 831, December.

- See “Public responses to the call for the public feedback on the evaluation of the TBTF-reforms”, FSB June 2019: https://www.fsb.org/2019/06/public-responses-to-the-call-for-public-feedback-on-the-evaluation-of-too-big-to-fail-reforms/

- See “Evaluation of the effects of financial regulatory reforms on small and medium sized enterprise (SME) financing: Final report”, FSB Nov 2019: https://www.fsb.org/2019/11/evaluation-of-the-effects-of-financial-regulatory-reforms-on-small-and-medium-sized-enterprise-sme-financing-final-report/