Implications of the too-big-to-fail reforms for global banking Remarks by Claudia M. Buch, Vice-President, Deutsche Bundesbank prepared for the IIF-BPI Colloquium on Cross-Border Resolution & Regulation

Check against delivery.

- 1 Motivation

- 2 The capacity of globally active banks to absorb shocks has increased

- 3 There has been progress with regard to the feasibility and credibility of resolution

- 4 This progress has not come at the expense of lending to the economy or increase fragmentation of financial markets

- 5 More needs to be done

- 6 Further reading

1 Motivation

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, the G20 endorsed a number of reforms intended to make the financial system safer. A core element of these reforms are policies that are addressing the “too-big-to-fail (TBTF) reforms” in order to reduce moral hazard and systemic risk. These reforms include standards for additional loss absorbency through capital surcharges and requirements for total loss-absorbing capacity, recommendations for enhanced supervision and heightened supervisory expectations, and policies to put into place effective resolution regimes and resolution planning to improve the resolvability of banks.

Many of the systemically important banks affected by these reforms operate across borders. Effective policies to address the too-big-to-fail issue thus require international policy coordination, and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) plays an important role in this regard. Whether a bank is considered to be globally systemically important is based on an internationally agreed set of criteria. On this basis, the FSB publishes an annual list of about 30 globally systemically important banks or G-SIBs. In addition, there are domestic systemically important banks or D‑SIBs. These are designated by their home authorities, and their number stood at 132 at the end of 2018. FSB standards provide that host authorities should impose internal total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) requirements for material sub-groups of systemically important banks residing in their jurisdiction. Resolution plans are in place, cross-border crisis management groups have been established for all G-SIBs, and home and host authorities have signed institution-specific cross-border cooperation agreements for most G-SIBs.

The Financial Stability Board is evaluating these too-big-to-fail reforms for systemically important banks. On 28 June the FSB published a report for consultation. The consultation closes on 30 September, and responses from a wide range of stakeholders are highly welcome.

The main findings of the evaluation can broadly be summarised as follows:

- Indicators of systemic risk and moral hazard have fallen. Systemically important banks are much better capitalised and have built up significant loss-absorbing capacity. Their funding costs now appear to reflect the probability of a bail-in in the event of failure.

- Effective TBTF reforms bring net benefits to society. Not only are banks more resilient, there are also no signs of material negative side-effects. And in particular, there has been no reduction in the aggregate supply of credit to the real economy.

- There are still gaps that need to be addressed. Some obstacles to resolvability remain, and there are gaps in information available to market participants and to public authorities.

In these remarks, I would like to focus upon the implications of the too-big-to-fail reforms on global banking.

2 The capacity of globally active banks to absorb shocks has increased

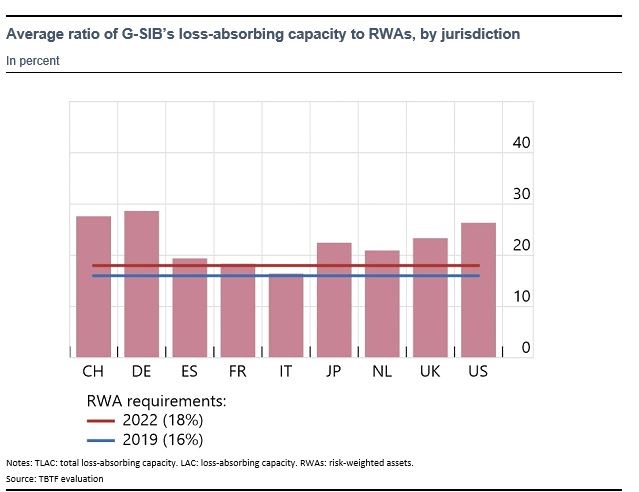

Two reforms within the scope of the evaluation are intended to increase the capacity of G‑SIBs to absorb losses, both as a going concern and in resolution. On a going-concern basis, G-SIBs are subject to capital surcharges that range from 1% to 2.5% of risk-weighted assets, or RWAs. These requirements must be met with the highest-quality type of capital, Common Equity Tier 1. G‑SIBs must also meet requirements for loss-absorbing capacity in resolution. The minimum TLAC requirement, which is expressed as a ratio of both risk-weighted assets (RWAs) and the Basel III leverage exposure measure, is being phased in between 2019 and 2022.

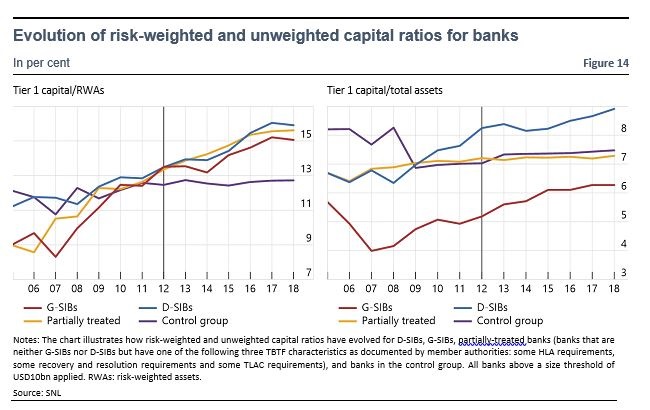

In terms of capital, clear progress has been made. The Tier 1 capital ratios of G-SIBs have doubled since 2011. Over the same period, leverage ratios have nearly doubled as well. Nevertheless, and notwithstanding differences in data sources and measurement, G-SIBs on average tend to have lower ratios of capital to assets than other banks. Higher equity capital, lower risk, and higher funding costs for systemically important banks would be expected to lower banks’ return on equity. In this sense, lower bank profitability may be in line with a more robust banking system and with lower costs for the taxpayer. Before the 2008 financial crisis, banks that were considered to be too-big-to-fail in effect enjoyed an implicit subsidy from the state. This is a costly economic distortion, and the reforms aim to reduce this subsidy. If the reforms are having an impact, we would expect to see the profitability of G-SIBs fall relative to other banks, all other things equal. At the same time, low profitability may also be an indicator of excess capacity in the banking sector and lack of exit – an issue that resolution reforms may help to address.

In terms of bail-inable debt, there has been clear progress as well. G-SIBs have issued large quantities of such debt and are meeting their minimum requirements for such loss-absorbing capacity. As at the end of 2018, in advanced economies, all G-SIBs designated before the end of 2015 had ratios of TLAC to RWAs above the 2019 transitional minimum, and 21 out of the 26 G-SIBs analysed already had ratios above the 2022 steady-state minimum. The results for the TLAC leverage ratio were even more encouraging.

3 There has been progress with regard to the feasibility and credibility of resolution

Another central plank of the reforms has been the establishment of resolution frameworks. Resolution is a way for authorities to deal with a failing bank without bailing it out and without interrupting its critical economic functions – typically by imposing losses on shareholders and creditors. Almost all jurisdictions that are home to G-SIBs now have comprehensive bank resolution regimes that align with the global standard – the FSB Key Attributes. They have almost all introduced comprehensive bank resolution regimes and are now carrying out very detailed resolution planning. This gives authorities a range of options for dealing with banks in stress.

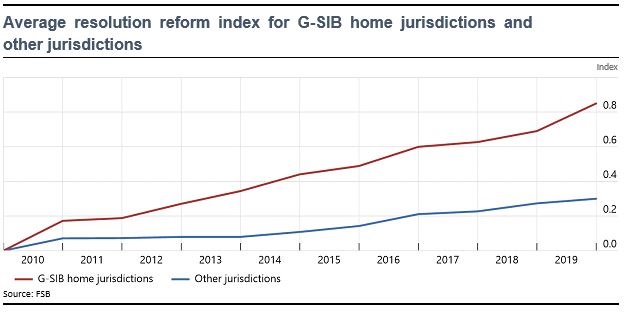

The evaluation has developed a resolution reform index, which is published on the FSB website.[1] The index ranges between 0 and 1, where 0 represents no implementation and 1 represents full implementation. It has been used in a number of analyses described in the consultation report.

Evidence from market prices and credit ratings suggest that resolution reforms are seen as credible by market participants. That is, market participants think that there is some probability that, in the event of a bank failure, losses would be imposed on shareholders and creditors rather than on taxpayers. Market prices suggest that investors think that they may suffer losses in the event of a bank failure and are pricing the risks accordingly. This is likely to be affecting the behaviour of banks as a going concern – so we do not have to observe an actual “failure” to observe effects of the reforms

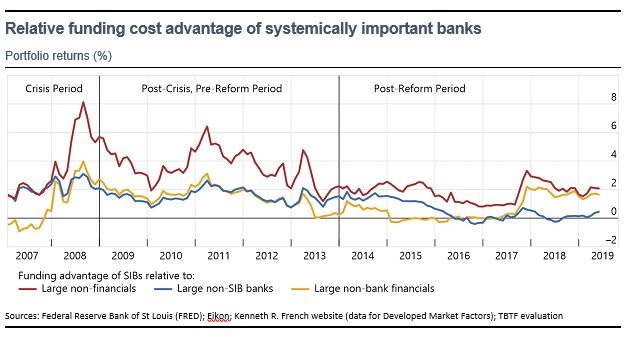

Changes in perceptions of the credibility of resolution are obviously hard to measure, and the evaluation has used different proxies. These include estimated G-SIBs’ funding cost advantages by looking at prices of bonds, credit default swaps and equities. Inevitably, the results are not identical. Generally, they show that funding cost advantages peaked during the global financial crisis and have since fallen, although not below levels seen before the crisis. Lower funding cost advantages indirectly suggest that the implicit funding subsidy has fallen.

Estimated funding cost advantages are also typically lower in jurisdictions that have implemented resolution reforms more fully, as measured by the resolution reform index. This suggests that more comprehensive implementation of resolution reforms is associated with a reduced funding advantage for SIBs, and hence with less economic distortion. In addition, the evaluation has looked at credit ratings and bail-in premia implicit in credit default swap (CDS) spreads, which are larger for riskier banks. Both of these results suggest that market discipline has improved.

4 This progress has not come at the expense of lending to the economy or increase fragmentation of financial markets

Generally, the evaluation finds that the benefits of the reforms significantly outweigh the costs. The evaluation looked at broader effects of reforms on the financial system and on the real economy, and it looked at costs and benefits from the social perspective, which is not the same as the perspective of the private sector. For example, successfully lowering implicit subsidies means higher funding costs for banks – but at the same time lower costs for taxpayers.

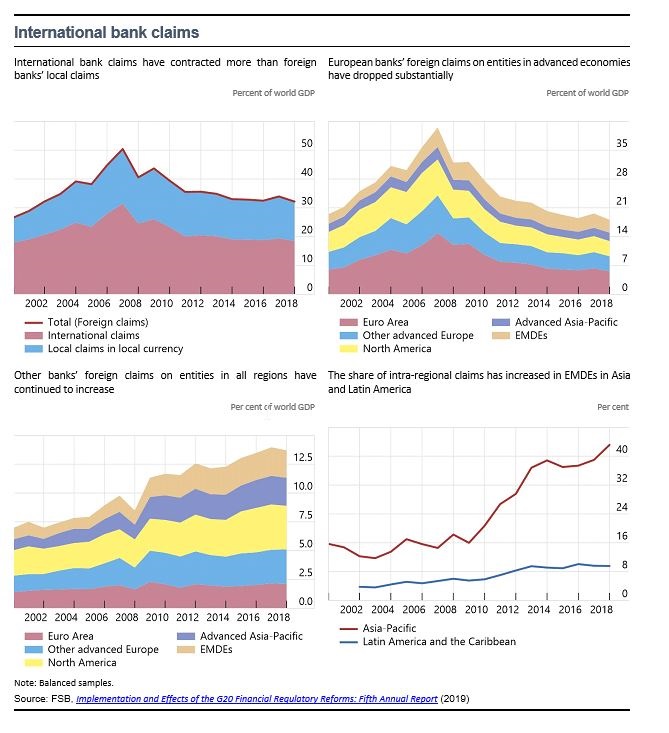

The financial crisis has slowed down, but not reversed, the long-term trend towards global financial integration. The aggregate retrenchment in international banking since the crisis stems from a decline in cross-border lending by European banks. Cross-border lending between other regions has continued to expand. At the same time, lending by international banks has shifted to more stable locally-funded sources in local currencies. Cross-border lending by advanced economy banks to borrowers in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) has grown since the crisis, and intraregional lending has also increased within EMDEs, in particular in Latin America and Asia.

There is no evidence that the implementation of TBTF reforms has reduced cross-border lending. Total syndicated lending, for example, has been increasing after a sharp drop in 2009. While G-SIBs lend to foreign borrowers more than other banks do, the proportion of foreign lending is relatively stable for both groups (fluctuating between 55% and 65% for G-SIBs and between 30% and 40% for other banks). Measures of cross-border connectedness reached peak values at the onset of the financial crisis and, after a sharp drop in 2008, have returned to or surpassed their pre-crisis levels.

Some respondents to a call for public feedback launched in 2019 argued that in particular internal TLAC requirements could drive market fragmentation.[2] It should be noted that the role of internal TLAC is to ensure that material subsidiaries have sufficient loss absorbing capacity. But there are trade offs. As FSB Chair Randal Quarles put it last year, “host authorities want certainty and home authorities want flexibility.”[3] According to the TLAC term sheet, each material sub-group must maintain internal TLAC of 75% to 90% of the external TLAC requirement that would apply to it if it were a resolution group. This may be higher than what individual banks would choose, and it would be higher than what we would observe in a fully integrated market. But from a social policy perspective, pre-positioned resources have value: The fully integrated market is not the right benchmark. In times of crisis, there are incentives to use the first mover advantage and hoard funds. Internal TLAC prevents this and encourages supervisory coordination. Hence, internal TLAC supports orderly cross-border resolution and serves as a coordination device to diminish host authorities’ incentive to ring-fence in resolution. That said, hard evidence on the effects of internal TLAC is not yet available. G-SIBs have not published information on TLAC in a consistent manner and information about internal TLAC is not available.

5 More needs to be done

Overall, the results of this evaluation show that the too-big-to-fail reforms have contributed to make the global financial system in general and global banking more resilient. Although the evaluation does not cover the current period of stress in the COVID-19 pandemic, the current situation clearly reveals the benefits of having resilient financial institutions that can buffer shocks. The pandemic represents the biggest test of the post-reform financial system to date, as it has pushed the global economy into a recession of uncertain magnitude and duration. The rapid and coordinated response by fiscal, financial and monetary authorities has mitigated the impact of the shock on the real economy and the financial system. However, the effects of the pandemic continue to put the financial system under strain. The findings of the report suggest that TBTF reforms have contributed to the resilience of the banking sector and its ability to absorb, rather than amplify, shocks. Major banks are much better capitalised, less leveraged and more liquid than they were before the global financial crisis. Systemically important banks in advanced economies have built up significant loss-absorbing and recapitalisation capacity by issuing instruments that can bear losses in the event of resolution. In response to the pandemic, the analytical work will be updated.

Given all these benefits, the new regime for the regulation and resolution of systemically important banks is also fairly new, and we are learning how it is operating. This experience reveals room for improvement of the current system and issues that warrant ongoing monitoring. The report focuses on the following gaps:

- Obstacles to resolvability remain, and these remain high on the agenda of the FSB and its members.

- Information systems can be improved further in order to enhance ability of markets, authorities, and other stakeholders to assess the functioning of the system.

- Compared to G-SIBs, relatively little is published by national authorities and at the global level about D-SIBs’ characteristics or the regulations to which they are subject.

- Risks arising from the shift of credit intermediation to non-bank financial intermediaries should continue to be closely monitored.

6 Further reading

FSB TBTF consultation report:

https://www.fsb.org/2020/06/evaluation-of-the-effects-of-too-big-to-fail-reforms-consultation-report/

FSB evaluation framework:

https://www.fsb.org/2017/07/framework-for-post-implementation-evaluation-of-the-effects-of-the-g20-financial-regulatory-reforms/

Findings of earlier evaluations:

https://www.fsb.org/2019/11/evaluation-of-the-effects-of-financial-regulatory-reforms-on-small-and-medium-sized-enterprise-sme-financing-final-report/

https://www.fsb.org/2018/11/incentives-to-centrally-clear-over-the-counter-otc-derivatives-2/

- See “Public responses to the call for public feedback on the evaluation of too-big-to-fail reforms”, FSB June 2019: https://www.fsb.org/2019/06/public-responses-to-the-call-for-public-feedback-on-the-evaluation-of-too-big-to-fail-reforms/

- Quarles, R K (2019): “Government of Union: Achieving Certainty in Cross-Border Finance”, remarks at FSB workshop, September.