Annual accounts for 2024 Statement at the press conference presenting the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Annual Report for 2024

Check against delivery.

1 Introduction

Ladies and gentlemen,

A warm welcome to you from me as well.

Before we start looking at the 2024 annual accounts together in a few minutes, allow me to make a few introductory remarks.

The President has already said it: the monetary policy measures of the past few years are still having an effect. They are also reflected on central banks’ balance sheets.

As you know, the Bundesbank started making provision for the increased financial risks early on, in the annual accounts for 2016. These risks materialised yet again in 2024.

On balance, the Bundesbank posted losses of around €19.8 billion in 2024, after a loss of €21.6 billion in the previous year. In 2023, however, we recorded a net distributable profit of zero because we used all of our provision for general risk and some of our reserves to offset losses. For 2024, remaining reserves totalling €0.7 billion were still available to offset some of the loss. The Bank is thus reporting an accumulated loss of €19.2 billion for 2024.

Let me share three important messages:

- We have reached the peak of the losses.

- Net equity has climbed to more than €250 billion.

- There is a revaluation reserve of over €260 billion for the gold.

So the Bundesbank’s balance sheet is sound.

The positive message is that the Bundesbank is fully able to perform its tasks even in the face of losses.

This slide shows that the Bundesbank’s net equity increased significantly, rising by €50 billion or roughly 25%. We will look at the development of net equity in detail in just a moment.

Now let’s take a closer look at developments in the annual accounts for 2024.

2 Balance sheet

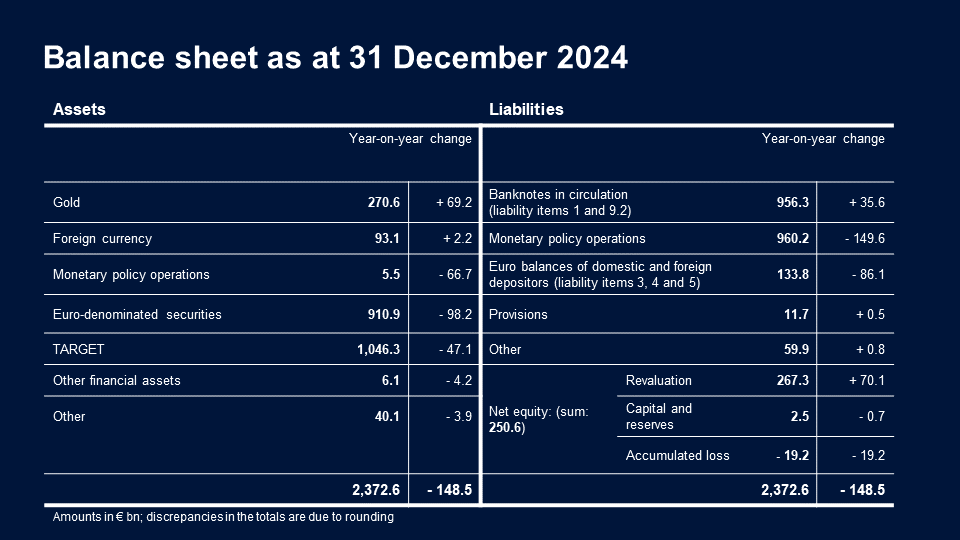

First, let’s look at the assets side of our balance sheet:

Total assets once again declined as a result of monetary and foreign exchange policy activities: they were down by around €149 billion, or 5.9%. Viewed over multiple years, though, total assets are still up on the end of 2019 – that is to say, their level before the pandemic and before the start of the highly accommodative monetary policy.

As in the previous year, the decline in total assets has three main drivers on the assets side:

- First, securities holdings from the monetary policy purchase programmes decreased by €98 billion: this was largely concentrated on the APP portfolio, for which reinvestments of principal payments were discontinued as of July 2023. For the PEPP, meanwhile, reinvestments were gradually reduced to zero only as of the second half of 2024. We will see the effects of this more clearly in the 2025 annual accounts.

- Second, lending related to monetary policy operations contracted by €67 billion, above all due to the phase-out of the TLTROs conducted at particularly favourable interest rates during the pandemic.

- Third, liquidity outflows meant that the TARGET claim on the ECB fell by €47 billion in 2024.

On the liabilities side of the balance sheet, there was a corresponding significant decline in deposits: liabilities related to monetary policy operations fell on the year to €960 billion. In addition, other euro balances dropped on the year to €134 billion, mainly owing to smaller balances of non-euro area central banks.

Another key item on the liabilities side is banknotes in circulation: when the negative interest rate policy period ended in 2022, growth in the volume of banknotes in circulation within the Eurosystem had effectively come to a halt due to the higher opportunity cost of holding cash. Only in recent months has growth picked up again at individual national central banks. The Bundesbank’s share of the Eurosystem’s banknotes in circulation reported on the balance sheet under liabilities item 1 “Banknotes in circulation” rose to €389 billion. The volume of banknotes issued by the Bundesbank actually increased more than in the rest of the euro area. This can be seen in liabilities sub-item 9.2 “Net liabilities related to the allocation of euro banknotes within the Eurosystem”, which has risen to €567 billion.

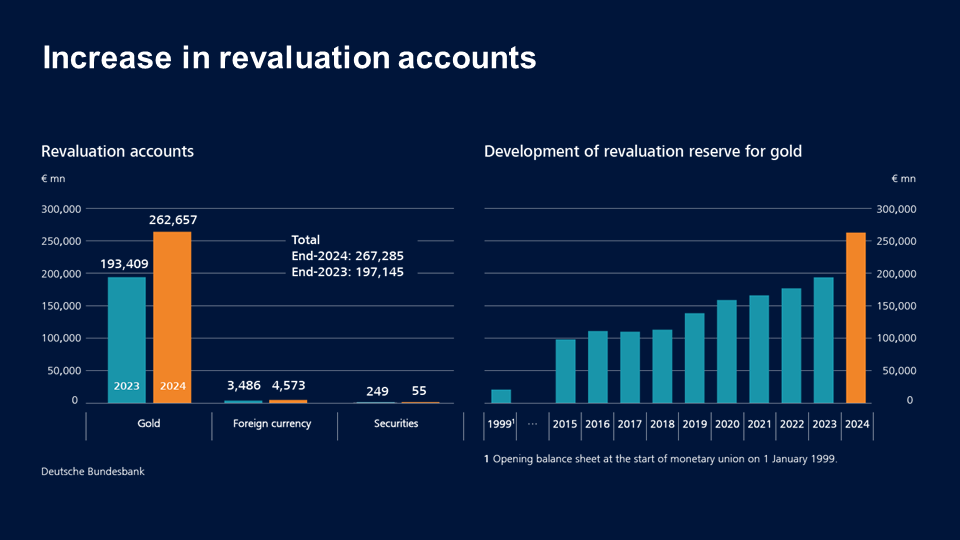

The third aspect I would like to discuss is the revaluation accounts item: this item increased on the year, climbing by €70 billion to €267 billion.

You will see a breakdown of the revaluation accounts item on the next slide.

The revaluation reserve for gold contained within that item has risen by €69 billion to €263 billion based on the market value of gold as at the reporting date. The revaluation reserve for gold has grown strongly when viewed over the long term, in particular. This revaluation reserve is currently almost thirteen times as high as its level when monetary union was launched at the start of 1999.

The revaluation reserve for foreign currency has increased by €1 billion, driven by the weaker euro. This growth is mainly attributable to assets denominated in US dollars.

The revaluation reserves also have an impact on net equity, as shown on the next slide.

Net equity comprises:

- capital and reserves;

- the provision for general risk;

- the revaluation accounts item; and

- as of the 2024 annual accounts, the accumulated loss.

Looking at developments over multiple years, we can see that net equity developed positively in 2020 and 2021 over and above the increase in the provision for general risk (rising from €186 billion to €197 billion). In 2022, net equity went up to €207 billion, even though the Bank released some of the provision for general risk. In 2023, the provision for general risk in the amount of €19.2 billion was fully released to offset losses; however, the decline in net equity was much smaller, at €7 billion. This was mainly because of further growth in the revaluation reserve for gold owing to movements in the price of gold. Given that the revaluation reserves are now at their highest ever level of €267 billion, net equity rose overall to €251 billion in the reporting year, despite the accumulated loss of €19.2 billion, and is now at an all-time high.

Having net equity of €251 billion shows that the Bank can absorb the existing and prospective losses. It is fully able to fulfil its mandate. Our balance sheet is sound.

3 Profit and loss account

Let’s now turn our attention to the profit and loss account.

Joachim Nagel has already pointed it out: the Bundesbank’s earnings situation has improved only slightly on the year. The turnaround in interest rates and the associated key interest rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 have set many things in motion. Much like in 2023, the combination of long-term monetary policy securities – generating low levels of remuneration – on the assets side and short-term deposits remunerated at higher rates on the liabilities side was a source of considerable strain in 2024.

The burdens arising from interest rate risk are affecting us via two channels this year:

- via our own securities holdings; and

- via securities carried on the balance sheets of the other national central banks in cases where these securities are subject to income and risk sharing and are thus included in the pooling of monetary income among national central banks.

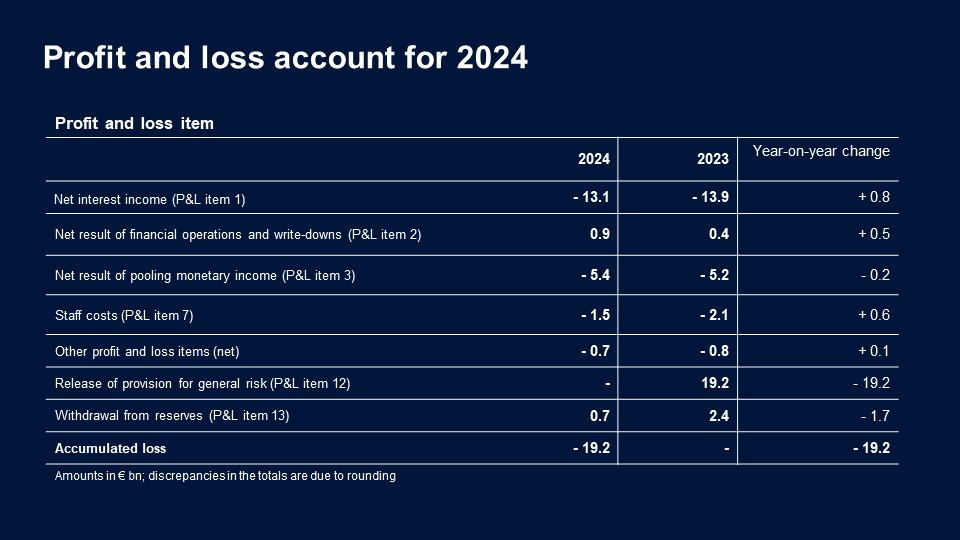

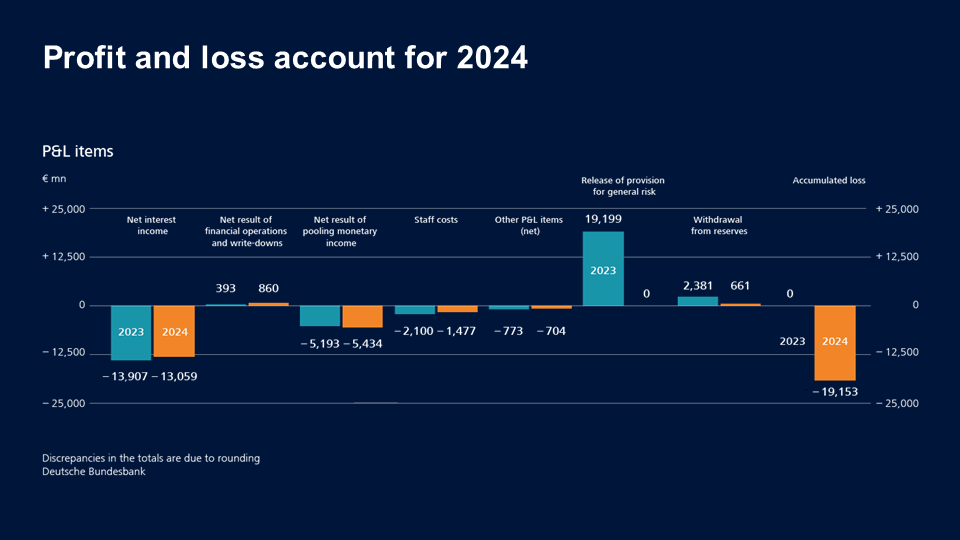

Now to the main items of our current profit and loss account:

The largest component of the profit and loss account isnet interest income. In bar 1, you can see that this has improved slightly, rising by €0.8 billion on the year. But at -€13.1 billion, it is clearly in negative territory, as it was in the previous year.

Why is that so? As already touched upon, the monetary policy asset purchases have given rise to longer-term fixed interest positions (generating a low level of remuneration). The counterparts of these on the liabilities side of the balance sheet – after deducting banknotes in circulation – are short-term interest-bearing deposits of commercial banks. The mismatch in maturities has left an open euro interest rate position on the balance sheet. The significant increase in the deposit facility rate in 2022 and 2023 is continuing to cause interest rate risk from this open interest rate position to materialise – putting net interest income under strain.

Specifically, this means that while the remuneration of monetary policy securities increased only marginally (to 0.54% on average), credit institutions’ monetary policy deposits resulted in a significant interest charge (of 3.81% on average for the year) owing to the higher deposit facility rate. This gives us a negative interest margin of -3.28% for 2024. On average for the year, this negative interest margin is actually up slightly on 2023 (-2.90%). However, maturing monetary policy securities, in particular, resulted in the open euro interest rate position being 22% lower on average for 2024, thus placing a lower burden on net interest income overall.

Realised gains arising from financial operations and write-downs related to foreign exchange and securities (bar 2) were, at €860 million, up by €467 million on the year on balance. Realised gains (mainly US dollars in the case of foreign exchange and US Treasury notes in the case of securities) – which were still coming under pressure from the stronger US dollar in the previous year – rose by €638 million to €1.2 billion in 2024.

At the same time, there were larger write-downs in the amount of €324 million. This is €171 million more than in the year before. While the need for write-downs on foreign exchange holdings was lower than in the previous year, there was a greater need for write-downs on securities holdings denominated in foreign currency, primarily as a result of higher capital market yields on US Treasury notes.

That brings me to monetary income. This comprises interest income from monetary policy assets, less interest paid on their counterpart liability items. In the Eurosystem, the resulting net interest income is shared according to the capital key.

At -€5.4 billion, the net result of pooling monetary income (bar 3) in 2024 was roughly the same as in the previous year. The lion’s share is still attributable to redistribution effects relating to monetary policy supranational securities. These are securities issued by supranational institutions, such as the European Union. These securities were purchased by other national central banks as part of PSPP and PEPP purchases. The Bundesbank itself has no holdings. The Eurosystem’s holdings came to an annual average of €398 billion. Income and risks are shared within the Eurosystem.

The supranational securities holdings generate only a low level of remuneration. Compared with the main refinancing rate, theinterest margin is thus negative at around -3.6% on an annual average for 2024. The lower income resulting from this for the affected national central banks is balanced out among the national central banks via the common pool of monetary income. Based on its capital share of 26.6%, the charge for the Bundesbank came to around €3.8 billion.

Staff costs (bar 4) in 2024 were down by €623 million to €1.5 billion. The decrease was caused by one-off effects in the previous year, in which additional transfers to staff provisions were necessary.

For 2024, this initially results in a loss for the year of €19.8 billion, which is €1.8 billion lower than the loss in 2023 before releasing the provision for general risk.

In the previous year, however, it was possible to offset the loss by fully releasing the provision for general risk of €19.2 billion (bar 6) and making withdrawals from reserves to the tune of around €2.4 billion (bar 7). By contrast, there are only reserves of just under €0.7 billion left available to offset the loss in the reporting year.

The profit and loss account for financial year 2024 thus closed with an accumulated loss of €19.2 billion, which will be carried forward to 2025.

4 Conclusion

I shall now conclude my remarks by summarising the main takeaways.

The financial burdens remained considerable in 2024. We expect the burdens to subside significantly as early as 2025. Nevertheless, they will remain considerable.

The open euro interest rate position will shrink further in size now that reinvestments under the PEPP have now also been phased out. Monetary policy securities holdings will become smaller as they mature. In addition, the negative interest margin will decrease because the lower deposit facility rate will reduce the interest expense for credit institutions’ monetary policy deposits.

Overall, we expect to report losses and carry them forward for some time and that we will therefore be unable to distribute any profit for an extended period of time.

That brings me to the most important message of my speech today.

The Bundesbank has considerable assets. These are significantly in excess of its obligations. Our revaluation reserves, for instance, amount to €267 billion. Net equity comes to more than €250 billion.

In short, the Bundesbank can bear both the current and the foreseeable financial burdens. What this shows is that the Bundesbank remains able to fully discharge its tasks even with an accumulated loss.

The Bundesbank’s balance sheet is sound.

Thank you.